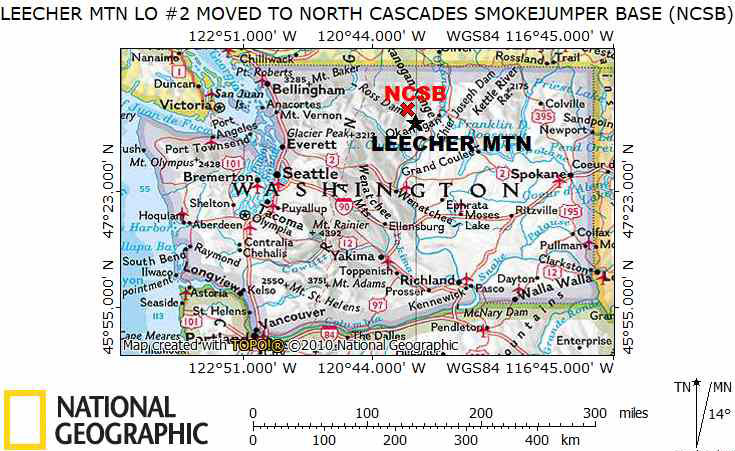

REGIONS: ORIGIN SITE ~ North Central WA, RE-LO SITE ~ North Central WA

When the 2nd Leecher Mountain Lookout was replaced in 1954, its steel tower was moved to the North Cascades Smokejumper Base (NCSB) where it was used in the reconstruction of a smokejumper’s training tower. This is an example of a Type 3 Re-Location which is defined when a fire lookout which is no longer being used for fire detection continues to be used for fire detection or fire suppression training at a new location. Like many Type 3 Re-Locations, the steel tower no longer exists as it was dismantled when a new training tower was built in the 1970s at the NCSB. The story of this re-location combines the complicated history of moves of fire lookouts, or parts of lookouts, to and from Leecher Mountain with the history of USFS smokejumping at NCSB, the “Birthplace of Smokejumping”.

History of the steel tower from Leecher Mountains 2nd lookout.

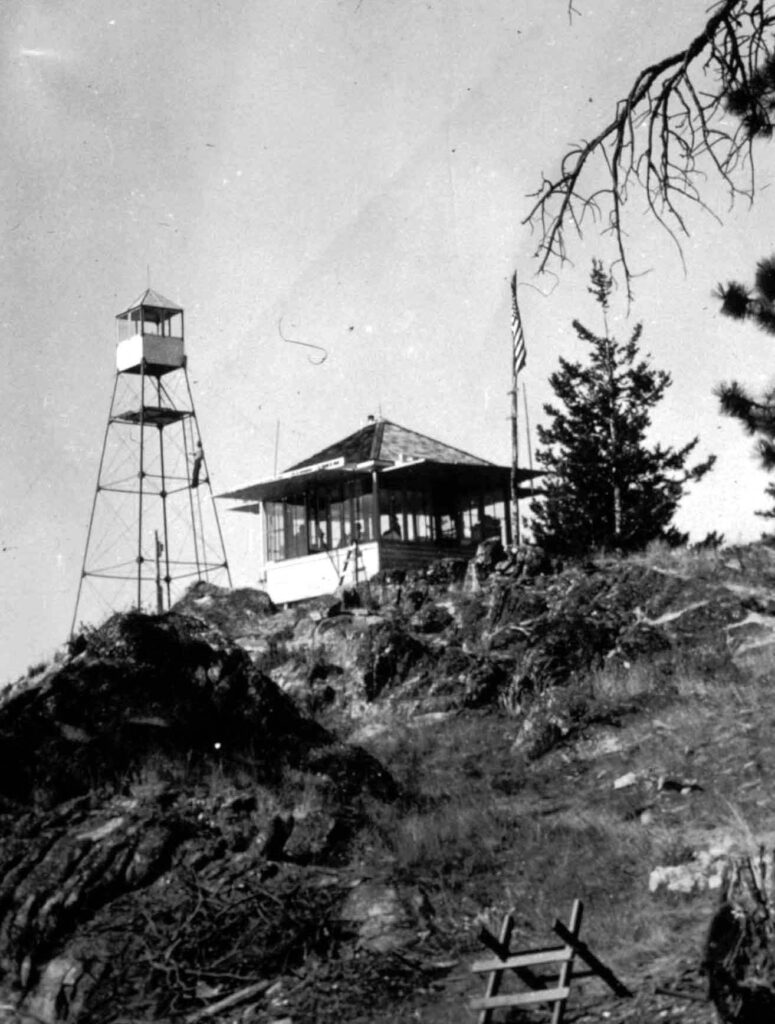

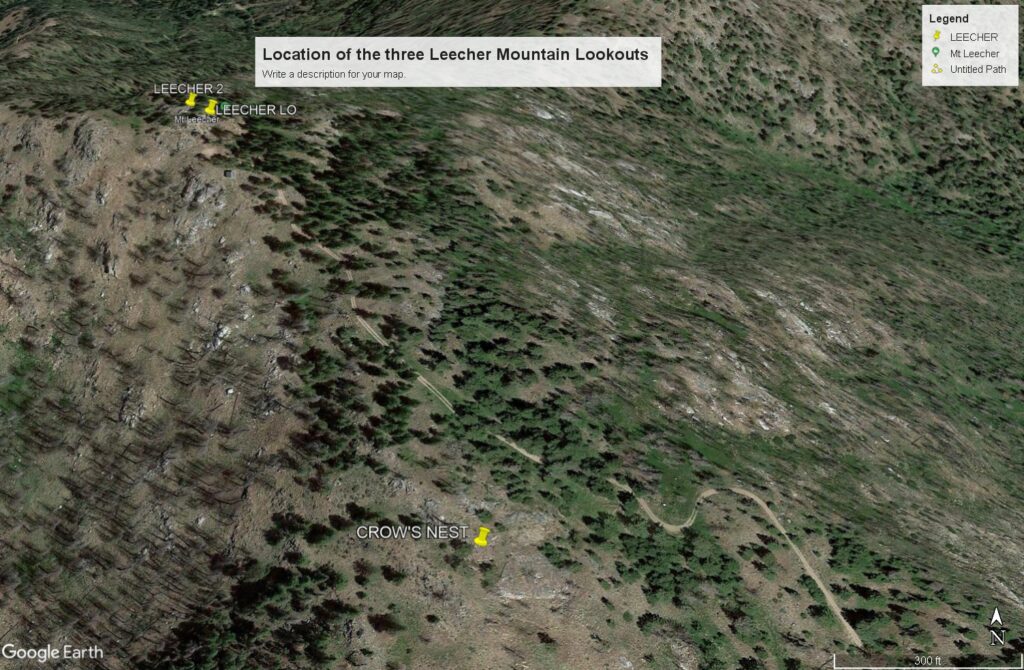

There have been three (or four) lookouts on, or near, the top of 5020’ high Leecher Mountain. This mountain, 9 miles SE of Twisp overlooks the Methow River Valley and the surrounding forested hills and grasslands. The first lookout was a crow’s nest platform in a tree on a high point about ¼ mile from Leecher Mountain’s 5020’ summit. The tree and remains of the crow’s nest platform and ladder still exist. The crow’s nest, which was first used as early as 1917, was replaced by a steel “windmill” tower with a 6’ x 6’ cab which was placed near the summit in 1922.

May 9, 1922: “The steel tower on Leecher mountain to be completed by the forest service June 15…will replace a tree which has been used for five years. While dangerous to life and limb and very uncomfortable in wind and sun, the old tree has thoroughly proved the point as worth of proper improvement. During five years more fires have been detected from this station than from any other, excepting possibly Stormy Mountain south of Lake Chelan.” (Okanogan Independent).

August 28, 1921: “Contract awarded for lookouts–The Coast Culvert & Flume company of this city (Portland) has been awarded a contract to build two steel lookout tops for the forest service. One of these will be located on Leecher mountain, in the Chelan national forest, according to announcement at the district forester’s office.” (The Oregon Daily Journal)

June 1922: “Rangers Pierpont and Price are helping erect a lookout tower on Leecher Mountain. The tower is 40 feet high and of standard construction.” (Six Twenty-Six)

October 1922: “Our lookout accommodations have been greatly improved this season by the addition of a steel tower 50′ tall with a cage on Leecher Mountain.” (Six Twenty-Six)

An 18’ x 22’ log cabin ground living quarters was built near the steel tower in 1922. An L-4 cabin replaced the log cabin in 1936.

While Bob Scott was attending Eastern Washington College of Education in the early 1940s, he worked for the U. S. Forest Service during the summers. He wrote about some of his adventures with the USFS. Bob served as a lookout on Leecher Mountain for a time at the beginning of the 1940 fire season. He described this in his writeup Leecher and Pearrygin. Bob wrote: “The lookout house was on the ground, down among the trees, but the fire finder was located in a six by six foot cab atop of a sixty-foot windmill tower. The iron ladder went straight up the tower and was only about a foot wide with half inch steel rods to climb on. My first trip up was with some trepidation, but after a few tries, by the second day, I was giving little thought to the height. On one trip down I was going too fast and slipped about four feet from the bottom. It jarred me enough to make me very cautious after that. There was a phone on the tower as well as in the ground house. Generally, the experience was satisfying, if nothing more than the great views I enjoyed. One evening, however, there was a forecast for possible thunderstorms. I figured that if a storm came up, I didn’t want to be climbing the tower in a lightning storm, so I lugged my sleeping bag up the tower and curled it around the fire finder stand. Luckily, no storm occurred, and all I had was a crick in my back from lying curled up around the base of the fire finder stand.”

Most references agree that the Leecher Mountain steel tower was moved to the North Cascade Smokejumper Base after it was no longer in use as a lookout on Leecher Mountain. However there are differences in the description of the replacement of the steel tower lookout and the date of the tower’s move. The Leecher Mountain entry in the FFLA web site firelookout.org reads in part: “In 1941 a live-in L-4 on an 11′ timber tower was built and the windmill tower moved to the Twisp Smokejumper Base for use as a training loft.” Rex’s Forest Fire Lookout Page in the web site firelookout.org does not mention a 1941 replacement lookout and reads in part: “In 1954, lots of moving of structures took place. The steel tower was moved to the North Cascades Smokejumper Base for a jump training loft.”

While the existence of the 1941 timber tower L-4 lookout is still in question, there is additional evidence that the steel tower lookout was still in place, and possibly in use, on Leecher Mountain until at least 1950 and then was removed before 1956. The NGS Data Sheet, which describes the placement of a triangulation station disk on the highest point of Leecher Mountain in 1925, also contains station recovery trip reports. The 1950 Coast and Geodetic Survey recovery note contained in the Data Sheet describes the route followed to the disk and reads in part: “…Follow main traveled road…to the lookout and station on the north side of the lookout house and 78.5 feet east of the steel lookout tower…” The 1950 recovery note also includes: “The Leecher Lookout House is a standard wooden building, 14 feet square and sits on the ground…The Leecher Lookout Tower is a steel tower 50 feet high and 20 feet square at the base.” There is no mention of an additional 11’ timber L-4 live-in lookout on Leecher in this 1950 recovery note. The Data Sheet’s 1956 recovery note reads in part: “NOTE—NGS description mentions a LOH and steel LOT which are no longer in existence. A new standard 14 x 14 LOH on a 50-ft tower now stands over station mark.”

The description given for the two photos below supports the belief that the steel lookout tower remained in place on Leecher Mountain into the 1950s. The description given in the Shafer Museum online photo archives reads “Leecher Mountain lookout and weather station August 8, 1951”.

Evidently, the Chelan National Forest was planning to rebuild the Leecher Mountain steel lookout tower in the early 1950s and continue to use the rebuilt tower on Leecher Mountain. A letter (shown below), dated February 24, 1953, from the USFS Region 6 office to the supervisor of the Chelan National Forest responded to an earlier proposal with plans to improve the lookout by increasing the height of the lookout tower. The Region office agreed that the present 28 feet tower could be extended to 41 feet by adding a new section to the base of the existing tower. The Region office also recommended that a standard 41 foot treated timber be used at Leecher and the 28 foot tower utilized at some other location. In 1954, a new timber tower, topped by an L-4 live-in cab, was placed on Leecher and the steel tower was moved to the NCSB.

A Note on Describing the Height of a Lookout: When different references describe the height of a given lookout differently, it can make the tracking of the history of that lookout difficult. In the case of the Leecher Mountain steel lookout, the height is usually described as 45’, but the heights of 60′, 50’, 40’ and in the case of the letter above as 28’ have been used. There can be many reasons for this variation. The height may have been accurately determined by examining the construction blueprints. Or the height may have been determined in the field. The accuracy of these field measurements can vary between those done with trained surveyors working with survey equipment to those done by eye-ball by those with little experience.

Another reason for reported differences is that there can be differences in the definition of what is being described. Some described the height of only the tower, often called the height to the cab floor or height to the catwalk. Some describe the height to the top of the walls of the cab, often called the height to the eaves. Some describe the height to the top of the cab roof, which may include a ventilator cap. A good example of the possible variation in these heights can be found in the Leecher NGS Data Sheet’s 1956 recovery note in which the survey crew describes the current Leecher Mountain Lookout as “a new standard 14 x 14 ft LOH on a 50 ft tower”. The description then continues with “Top of LOT is 55.2 ft, eaves are 49.2, and floor is 41.0 ft above station mark”. In this case there is more than 14 feet difference between these 3 descriptions and the commonly used 50 foot description is somewhere in the middle.

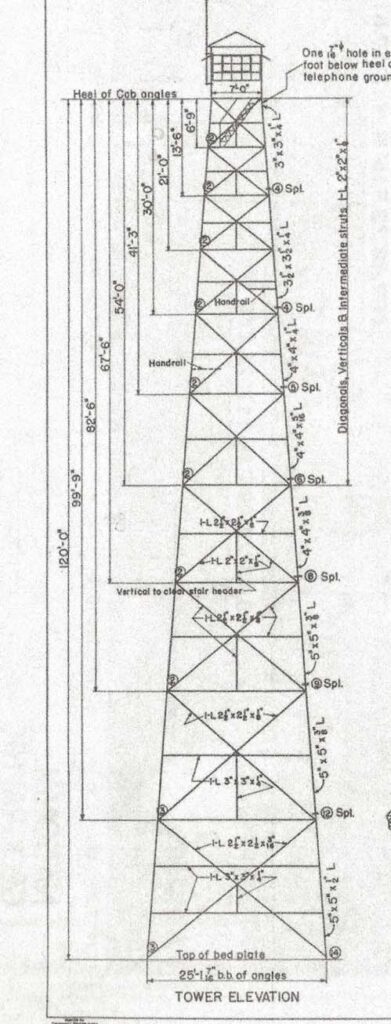

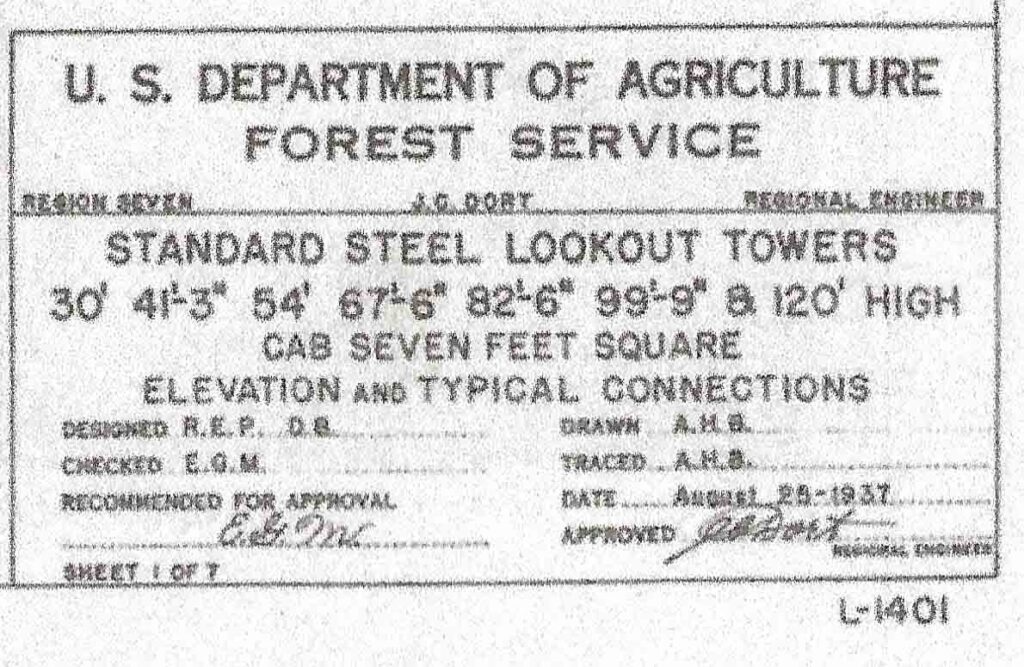

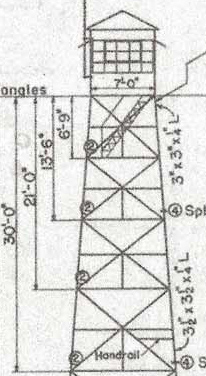

Next, consider building a steel lookout, similar to the 1922 Leecher steel tower lookout, using the Forest Service’s 1938 Standard Lookout Structure Plans. The tower elevation diagram for the Standard Steel Lookout Towers shows that towers ranging from 30 foot to 120’ high can be built by progressively adding lower sections to the shortest 30 foot, four section tower. Our lookout will start with a short 4-section, 30 foot steel tower to closely match the 1922 Leecher steel tower lookout. We will then add the standard 7’ x 7’ steel cab, which the 1938 plans show to be 7’ 6” from the floor to the top of the vertical walls. The cab roof and ventilator cap adds another 2+ feet to the over-all height. Our steel lookout now can be described as 40 ft to the top of the LOT, 37.5 to the eaves and 30 ft to the floor. While these numbers are not exactly the same as the heights quoted in different references for the Leecher Mtn steel tower lookout, they are close enough to help explain the quoted differences.

These heights describe the distance from the base of the tower legs. If the tower is installed on a raised base and/or tower footings the overall height can be several feet larger.

History of the NCSB and its jump training towers.

(NOTE: The USFS’s smokejumper base located near Winthrop, Washington has been known by several names over the years. It was given the current name of North Cascades Smokejumpers Base in 1967. I use that current name, or its widely used abbreviation NCSB, in the following writing. The Chelan National Forest initially managed the base. When the Okanogan National Forest was formed out of a portion of the Chelan NF in 1955, the Okanogan NF took over the management of the base.)

Soon after the formation of the United States Forest Service (USFS) in 1907, the use of aircraft in forest and wild fire fighting was being studied. It was considered by many too risky to fly the early planes over the western mountains. The U. S. developed more capable airplanes and built up the number of them in the mid-1910s. As early as 1915, fire detection flights were made for the USFS by the US Army Flying Service or by private pilots who were paid by the USFS. Supplies and fire-fighting tools were dropped from aircraft to active fire camps starting in 1929 and this method of cargo delivery was then improved by using parachutes for the drop. The USFS began to build airstrips within the national forests in the 1930s to be used to deliver cargo nearer to potential forest fire sites. Cargo delivery by air and the use of these remote airfields became part of the USFS’s firefighting strategy by 1936.

There were a few proponents in the USFS to drop firefighters by parachute to forest fires. A Utah forest ranger proposed this in 1934 and actually sponsored a few demonstration jumps by a professional parachutist. Most of those at the top levels of the USFS believed the idea to be too risky and crazy, so the proposal was turned down at that time. (The letter below demonstrates a typical response.)

In 1935, the USFS allocated funds for the Aerial Fire Control Experiment with the goal of determining whether wildfires could be retarded by dropping chemicals mixed with water from the air. The experimental flights were initially carried out in the USFS’s California Region using airplanes and pilots loaned by the army and leased from private owners. In 1938 the forest service bought its first plane, a 5-passenger Stinson, which they used to carry out the last of these experiments in the forests of Oregon State. A number of different fire-retarding chemicals and methods of delivering them were tried. The final conclusion of these experiments was that fire suppression by air was not feasible at that time due to the limited amount of fire-retardant that could be carried by available airplanes.

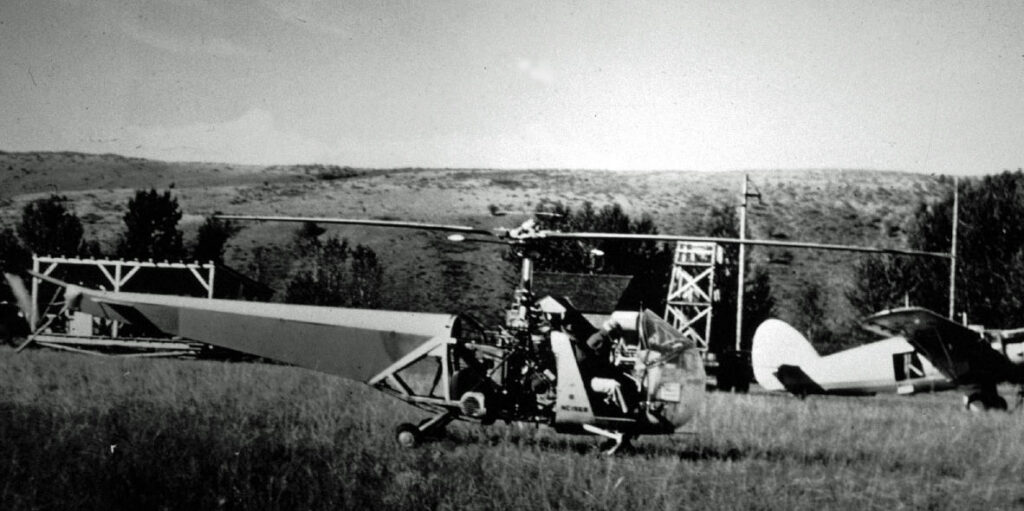

Funds remained at the conclusion of the Aerial Fire Control Experiment and the USFS now had its own airplane. In 1939, it was decided to use these remaining funds and the plane for the proposed Parachute Jumping Experimental Project. A goal of this project was to develop a method of safely dropping firefighters by parachute into fires in timbered areas in rough terrain and at high altitudes. It was decided that the experiment would be conducted out of the Intercity Airport near Winthrop, Washington by the USFS’s Pacific Northwest Region 6. This 3800 feet long dirt airstrip was chosen as it was already owned by the Chelan National Forest and was surrounded by forest and grasslands with elevations ranging up to 7000 feet and with a broad range of vegetation and terrain.

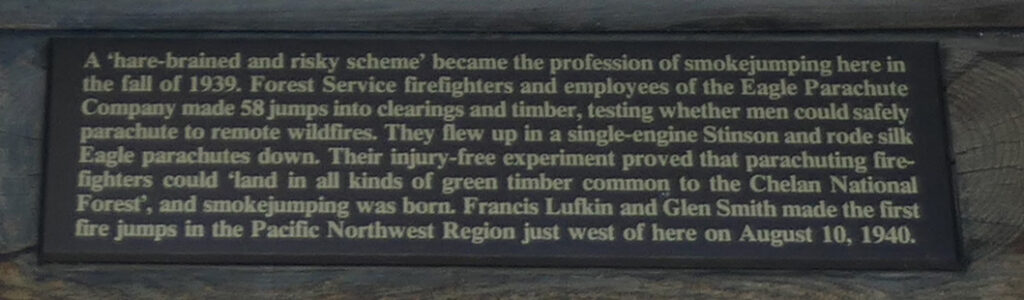

The project was carried out from October 5 and November 15, 1939. 58 live jumps made by 11 different jumpers demonstrated that properly trained and equipped firefighters could be safely parachuted into forested mountain terrain. These successful results led the forest service to establish two jump training centers, one in the Pacific Northwest Region 6 and one in Montana and Northern Idaho’s Region 1, in 1940. The Region 6 center was located near the banks of the Methow River at Winthrop’s Intercity Airport. The Winthrop base, now named the North Cascades Smokejumper Base, claims the right to be called “The Birthplace of Smokejumping” due to its role in the successful 1939 Parachute Jumping Project.

Region 6’s Winthrop base and Region 1’s base near Missoula, Montana both operated in 1940. Three experienced and one rookie smokejumper were trained at the Winthrop base and smokejumpers jumped to two fires out of there that year.

In 1941, lack of funds and manpower forced the USFS to limit their smokejumper program to one base. The Montana base at Ninemile, 20 miles west of Missoula, was chosen and all of Region 6’s jumpers and training were transferred from Winthrop to Ninemile. When jumpers were needed on Region 6 fires, they were dispatched from Montana. An aerial cargo loading operation was set up at the Winthrop Ranger Station and the Intercity Airport. Jumping was further limited during the WWII years as many of the experienced jumpers entered the armed forces.

In 1945, the Winthrop base at the Intercity Airport was reinstated as a permanent smokejumping operations and training center. The training of Winthrop smokejumpers continued at Ninemile through 1946. In the book Spittin’ in the Wind by Bill Moody and Larry Longley, Jim Allen, a 1946 NCSB Rookie smoke jumper describes his training. After being accepted as a smokejumper trainee, he was told to report to the Twisp Ranger Station. Jim then continues “…on a Sunday morning in May, 1946…We were signed up at the Twisp Ranger Station, and the following morning we were on the train to Montana to take our smokejumper training…In 1946 there were four jumper units and they all took their training at 9 mile, a training facility and airport, located 9 miles west of Missoula…After 3 weeks of training, we had all completed our 7 jumps and were on the train headed back to Winthrop.”

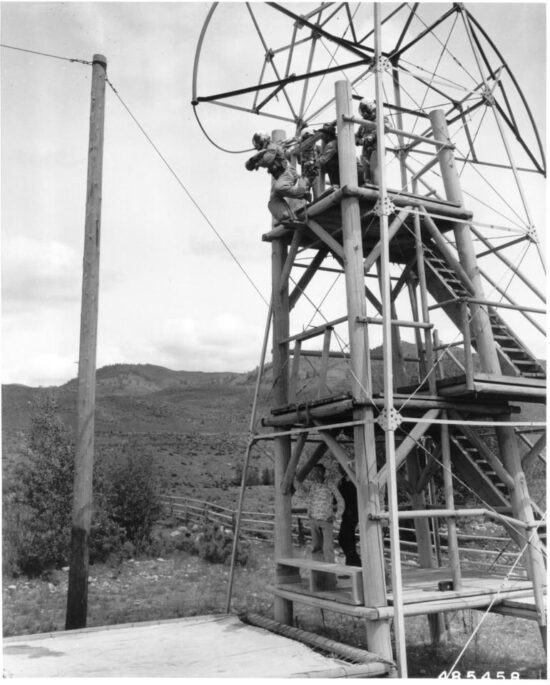

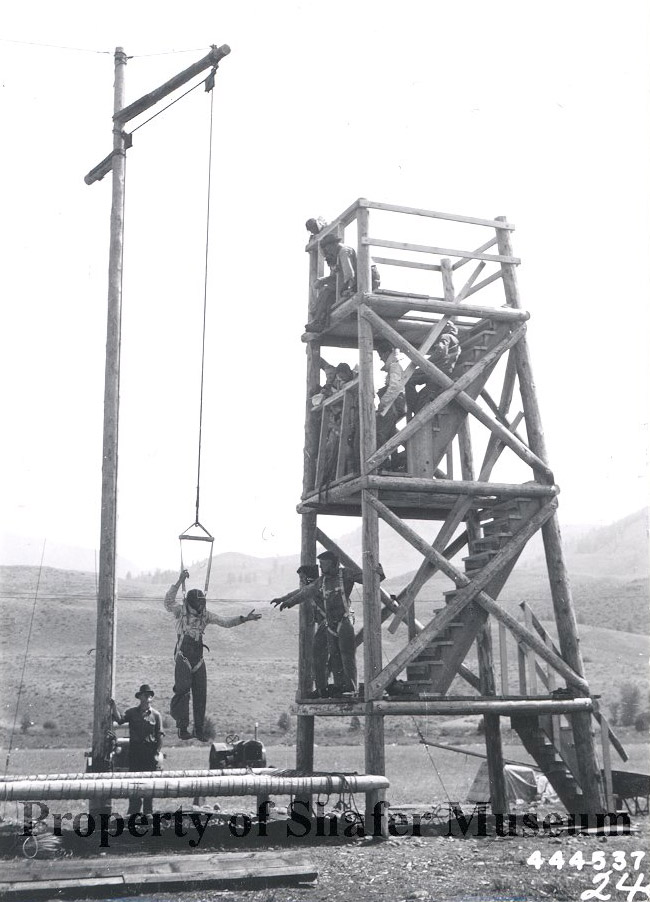

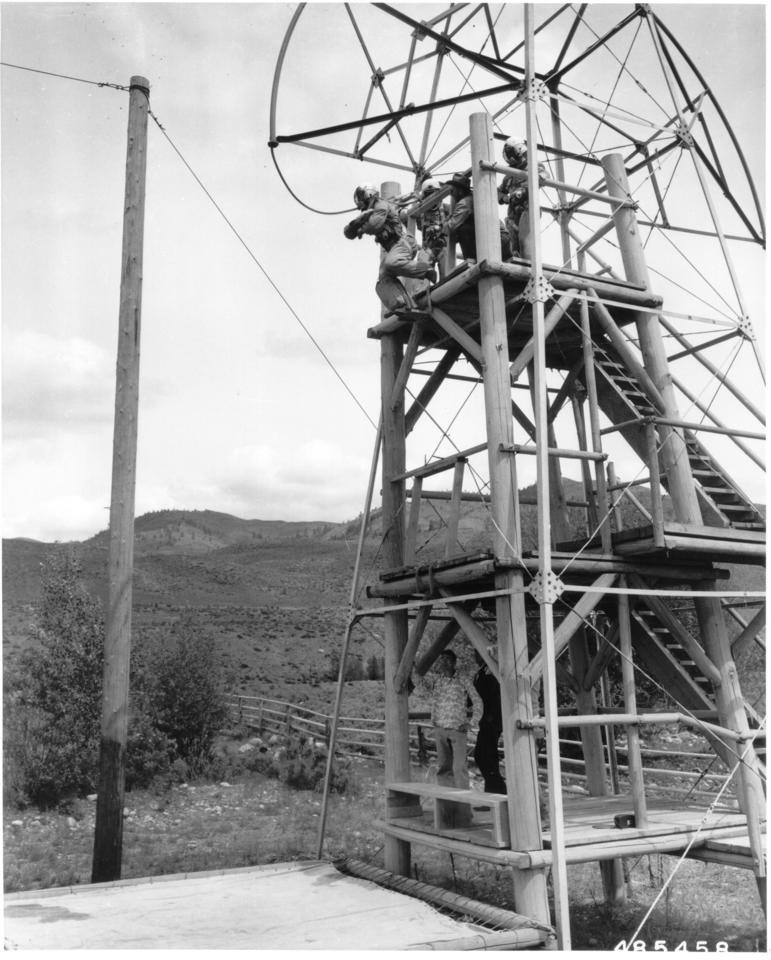

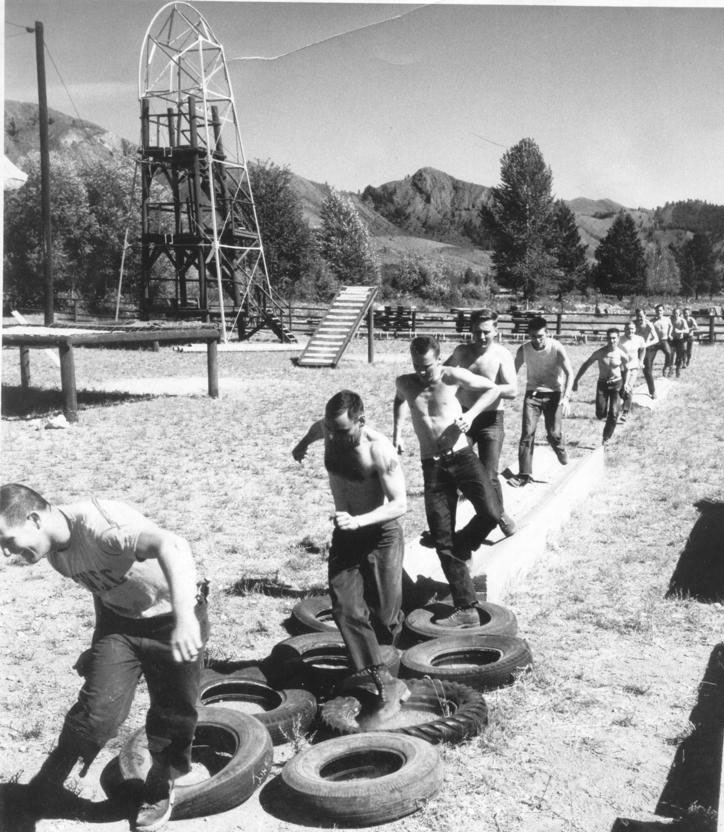

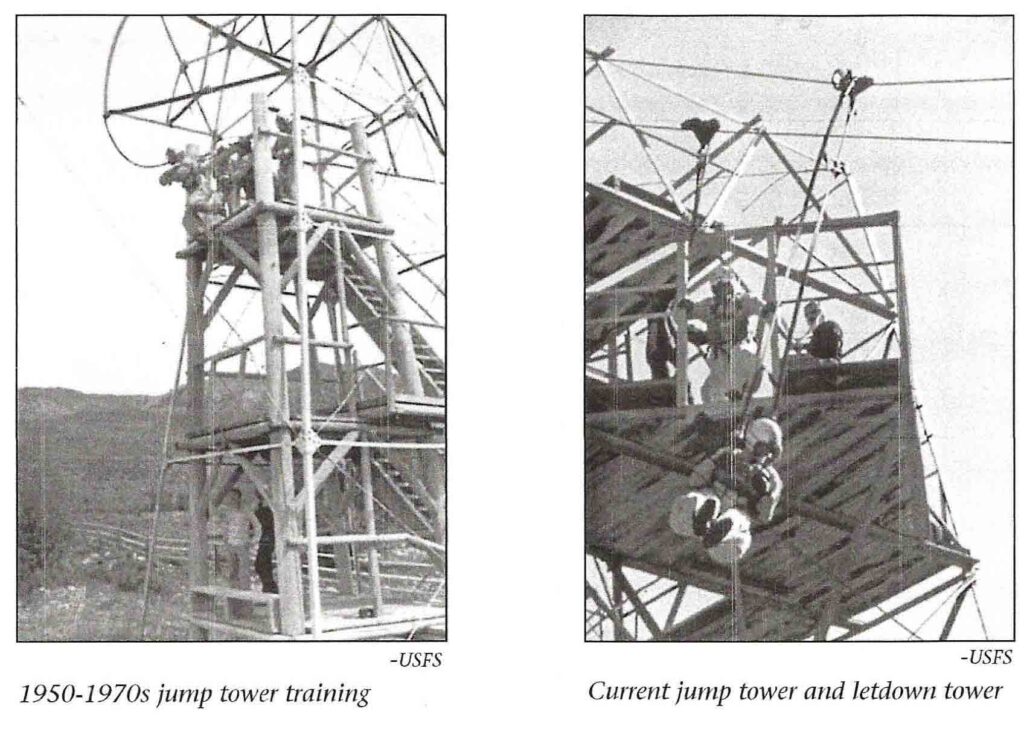

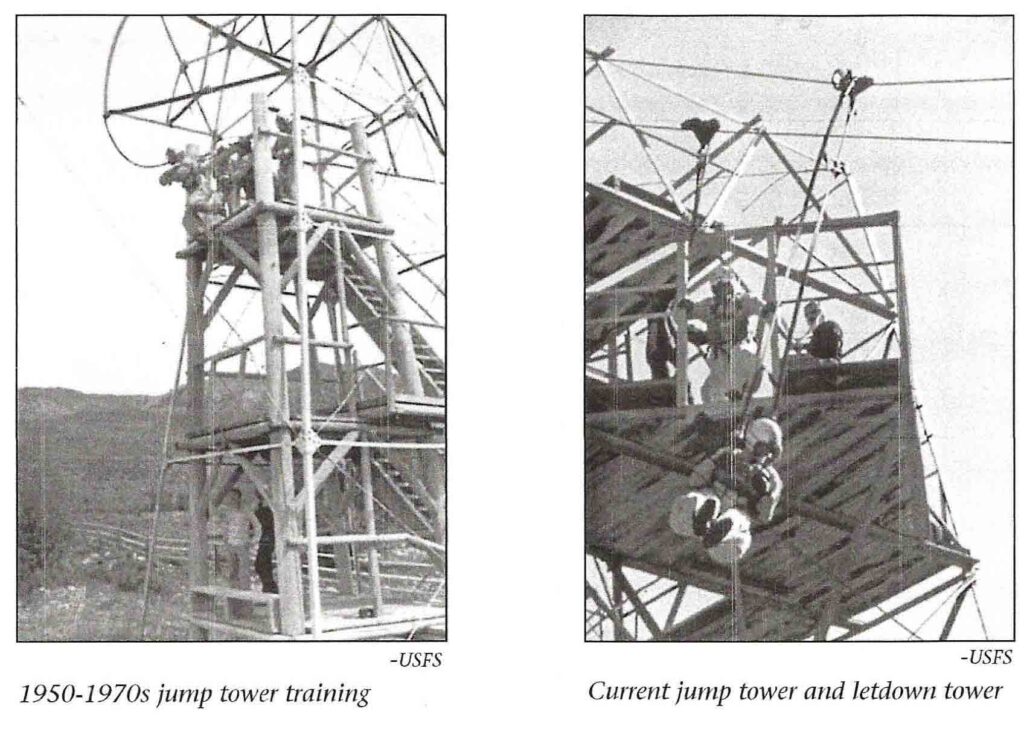

The training of NCSB jumpers was returned to the Winthrop base at the Intercity Airport in 1947. Roy I. Goss, another 1946 NCSB Rookie smokejumper, writes in Spittin’ in the Wind “1947 was a year of building our own training apparatus…in March, April and May…there were three or four of us falling trees…peeling them and cutting them in lengths for all the training apparatus. We built a jump tower, high letdown, rope climb and net, high and low ramps, overhead bars and the “TORTURE RACK”. A number of photos, apparently dated in 1947, shows this initial NCSB wooden pole jump tower and other training equipment.

In the spring of 1948, a flood destroyed the base’s training facilities located near the Methow River. The base was moved to its current location on the opposite side of the airport in 1949.

In 1954, the steel tower lookout on Leecher Mountain was replaced by a treated timber L-4 live-in lookout. The steel tower was moved from Leecher Mountain to the NCSB where it was used in rebuilding the base’s jump training tower. This improved NCSB tower was a “composite” which included both the wooden tower and the Leecher steel tower.

Dec 26, 2023 update:

Barry George, who is now a volunteer at the Okanogan County Historical Society, provided the photo above. Barry and I recently communicated by both phone and email. Barry had been a Smokejumper at NCSB starting with his Rookie training in 1973. He has also been the Asst. Fire Management Officer in the Methow Valley. Barry called this jump training tower the “shock tower” as it was used to simulate the opening shock of a parachute as well as serving to give trainees an opportunity to practice exit posture. He described the tower as a round wood pole tower with the steel windmill tower part of it. The steel tower held the rope that the trainee rode down on. Barry went on to add that he had jumped off this when he was training and that he worked on building the current tower when he was at NCSB.

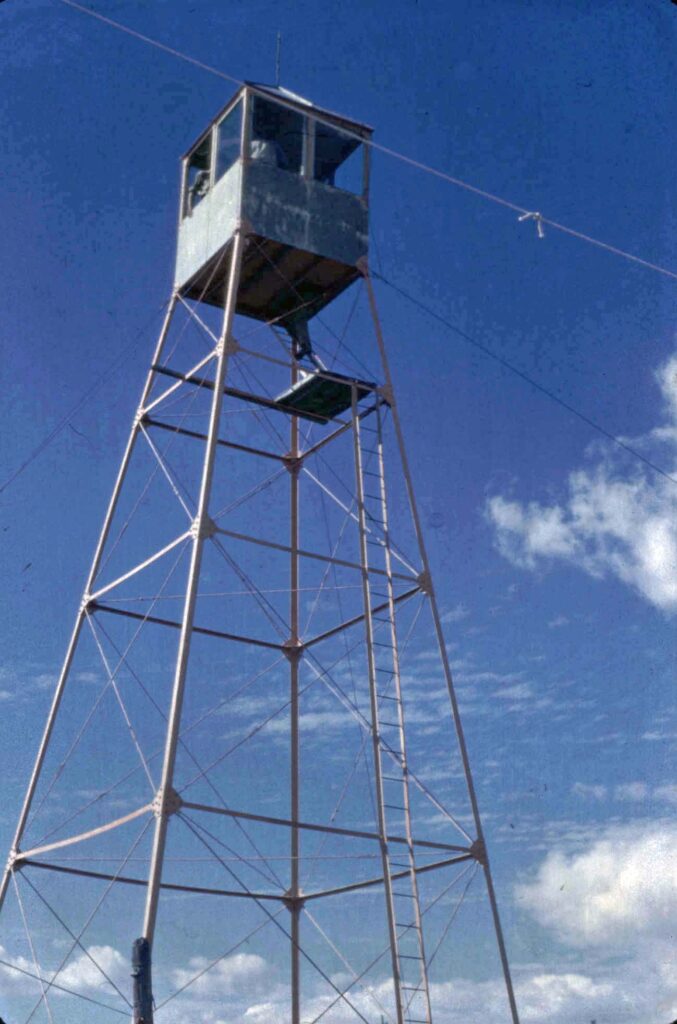

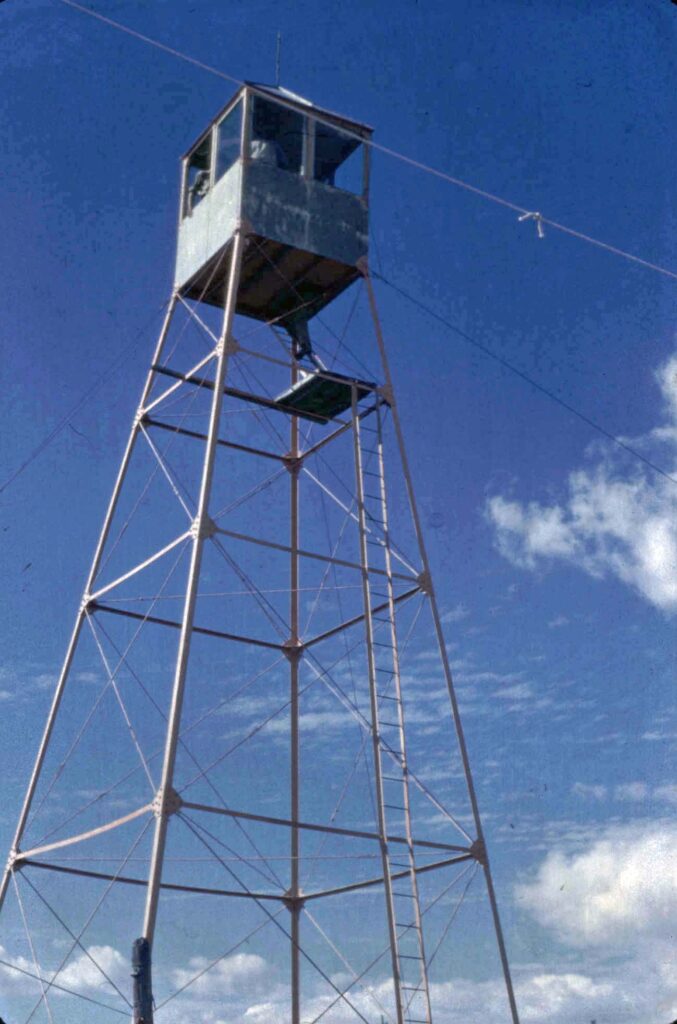

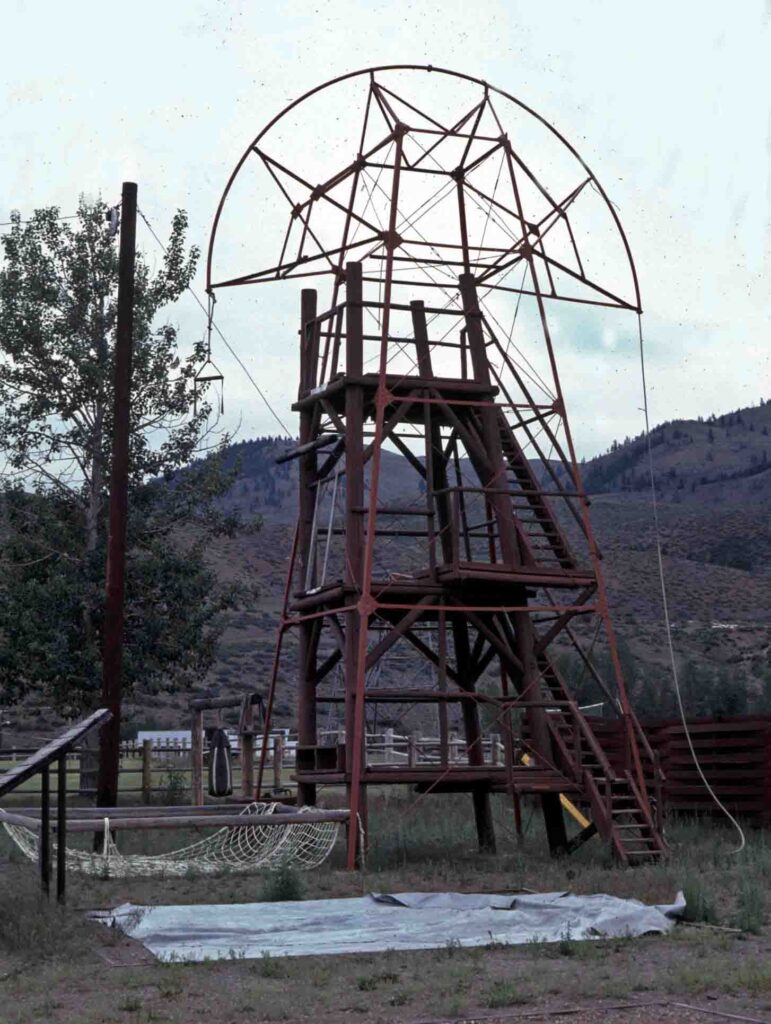

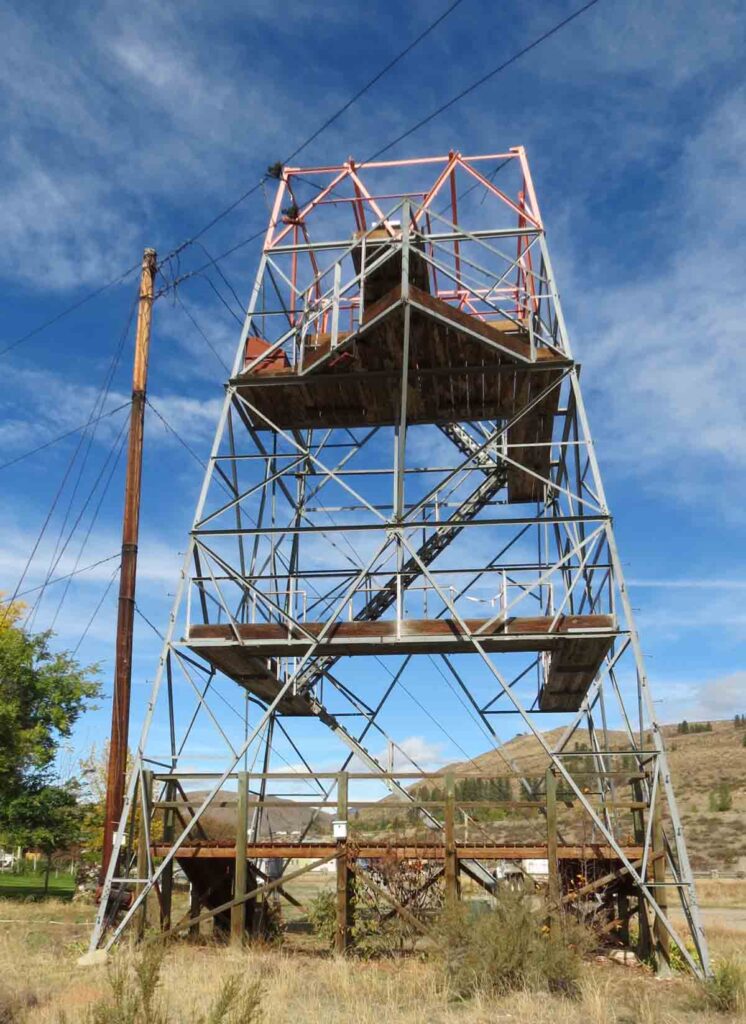

This rebuilt “composite” jump training tower was used for smokejumper training at the NCSB into the 1970s. It was then replaced by the current jump and letdown tower. We recently visited Bill Moody, who had been a NCSB Smokejumper from 1957-1989 and who had been the NCSB Base Manager from 1970-1989. Bill also wrote the book History of the North Cascades Smokejumper Base which was published by the National Smoke Jumper Association. Bill helped us fill in some of the history of the NCSB and its jump training towers. He told us that the current tower was built using a steel power line tower obtained from the Bonneville Power Authority (BPA). The old Leecher Mountain steel tower was taken apart and none of the steel was used in the current NCSB tower. The Leecher Mtn. tower steel was likely re-cycled. Bill believed that the current NCSB tower was built about 1974. Barry George , who had started at NCSB as a Rookie Smokejumper in 1973, confirmed Bill’s general time period for the construction of the current tower. Barry said that he had helped rebuild the one that’s now out at NCSB when he was there using an old Bonneville Power Administration high tension power line tower.

Our visit to the North Cascades Smokejumper Base, 10/4/2023

We visited the NCSB, the Re-Location Site for the Leecher Mountain steel tower, during an early October week-long fire lookout chasing trip based in Winthrop. We had two goals for this visit; 1) To look for the Leecher steel tower, or if no remains could be found to see if anyone on the base knew anything about its final fate; 2) To tour the base and learn more about the training and life of the smokejumpers.

The North Cascade Smokejumper Base web site contains the following invitation: “Birthplace of Smokejumping. Hosting tours from 11:00am – 3:00pm. Come take a tour guided by a real smokejumper at America’s first, still operating, Smokejumper Base. We are part of the US Forest Service and are dispatched to parachute into remote rugged terrain to reach wildfires before they become a bigger problem. We will show you our equipment and facilities and answer any questions you might have about our odd profession. If it’s cold outside it’s best to call ahead for availability, same for large groups.” We stopped one afternoon on our way back from visiting a nearby abandoned lookout site and found the NCSB office to be closed. When we phoned the base phone number, (509) 997-9750, from our Winthrop motel, we were able to book a tour for the two of us the afternoon of October 4th.

It is only 4 miles by a paved road from Winthrop to the base. While the sign for the base is obvious, it would be easy to miss it and drive on by. After turning off onto Intercity Airport Road, we saw the base’s high steel jump and letdown training tower in the field to the left. We soon reached the visitor parking area near the NCSB office .

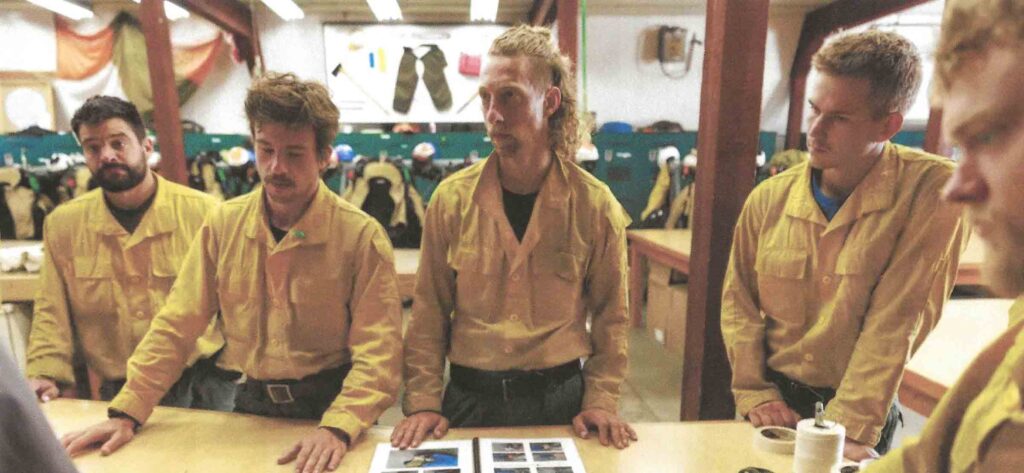

We checked in for the tour at the office and after exchanging bits of history and looking at photos of both the Leecher Mtn steel tower lookout and the NBSB, we met our tour guide, Tobiahs Shapiro. Tobiahs was one of the seven Rookie Smokejumpers who had graduated from the training at NCSB in June, 2023 after passing their qualifying ground training and 30 practice jumps. Since then, he has jumped into several fires.

The base’s office is near the edge of the airport’s 5050’ paved runway. While the name of the airport is now the Methow Valley State Airport, many still use the original Intercity Airport name. Originally owned by Okanogan County, the 3800’ dirt Intercity Airport was given to the American Legion in 1930. It was then sold to the Chelan National Forest in 1932. The USFS conducted the Parachute Jumping Experimental Project out of the Intercity Airport in 1939. The runway was lengthened and paved in 1966. In the 1980s, the USFS deeded the airport to Washington State and then the name was changed.

The buildings and training facilities of the Winthrop Smokejumper Base, which was established in 1940, were originally on the Methow River side of the runway. A spring 1948 flood washed them away. The base had been moved to its current location on the opposite of the airstrip by 1949.

The name of the base has also changed over the years. Many of the captions for the old photos call it the Winthrop Base. There have been several other name changes after the Okanogan NF was formed out of the Chelan NF in 1955. The 1957 photo of the base sign shown below shows one of these names. The official name was changed to the North Cascades Smokejumper Base in 1967.

Our tour began by walking with Tobiahs from the office past the dormitory and other base buildings toward the jump tower.

During our tour, we talked about how hard it is to become a qualified smokejumper. The first hurdle was becoming qualified to apply for training. The USFS requires applicants for smokejumper training to have at least one season of wild land fire suppression work as well as either a bachelor’s degree in forestry or related field or at least one year of experience in these fields. One USFS announcement for smokejumper recruitment noted that “due to the quantity of applicants, …applicants are encouraged to have at a minimum 4-5 years of wildland fire experience…” Tobiahs met the education requirement as he had gained a bachelor’s degree from the University of Washington’s School of Forestry.

Even though an applicant may meet these qualifications there are more applicants than available training openings. In Region 6, which encompasses the NCSB and Redmond, Oregon bases, there were 106 applicants in 2023 for rookie smokejumper positions. 19 were selected for training, 9 at NCSB and 10 at the Redmond, Oregon base.

The trainee needs to meet the Smokejumper Minimum Physical Standards in order to start training. These standards include; 1) 7 pull-ups or chin-ups; 2) 25 push-ups; 3) 1.5 mile run in 11 minutes or less; 4) Pack out – 110 pound pack for 3 miles in 90 minutes or less; 5) Standard Firefighting Pack Test for U.S. Forest Service. New trainees will have one opportunity to pass the test during the first day of training and the 110 pound pack test must be passed, in one attempt, no later than the first week of training. Except for the pack out and 1.5 mile run, the test shall be performed during one established time period with a break of not less than five minutes, nor more than seven minutes between events. Prior to the 1.5 mile run, employees shall be given a reasonable warm-up period.

The rookie trainees needed to successfully complete a six-week ground training course using the base’s training tower and to complete a demanding physical conditioning course before boarding an airplane for their first practice jump. Two of the nine NCSB candidates had washed out of the program before the first jump. The typical rookie washout rate is 30%.

As we neared the 60’ high, three-level steel tower, Tobiahs described how the tower and its attached cables were used in training how to exit the airplane (Exit Procedures), how to safely land (Landing Procedures) and how to get down if they get hung up in a tree during landing (Letdowns).

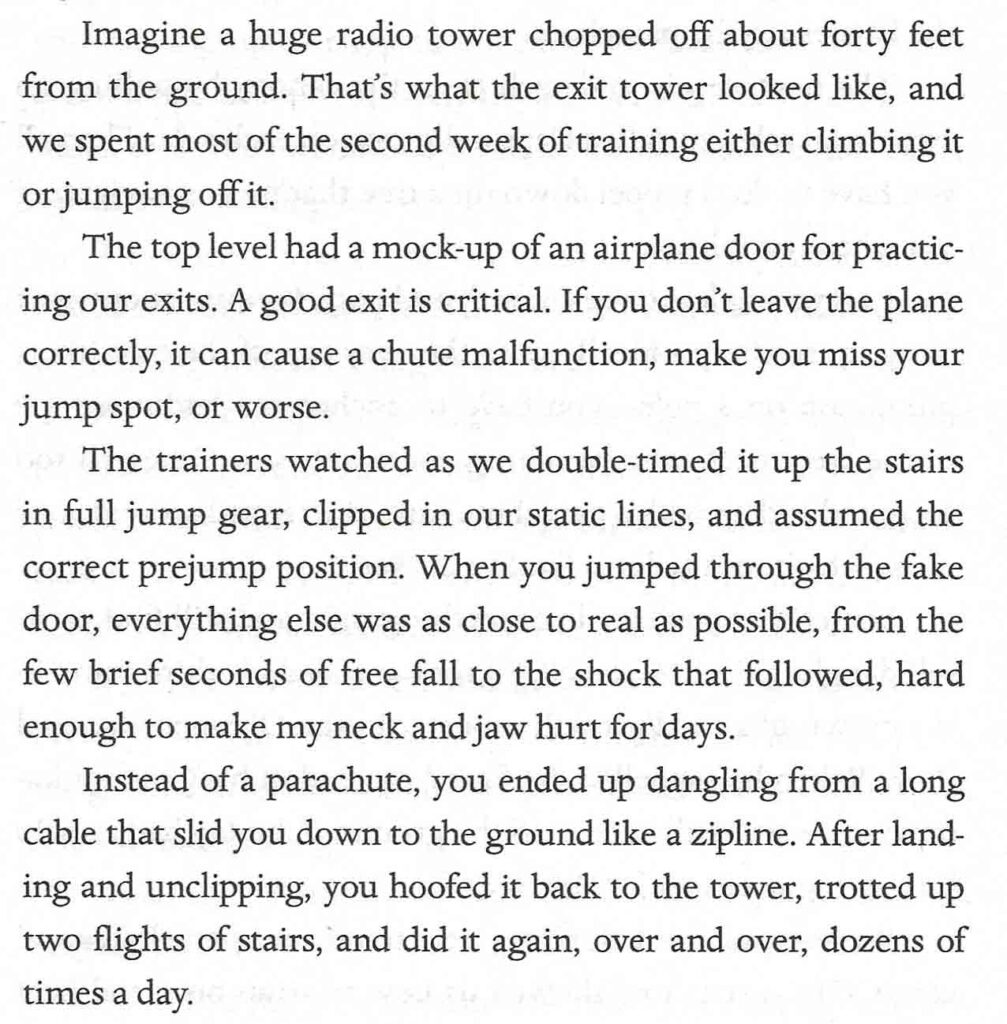

The Exit Procedure training is described in the book SMOKEJUMPER by Jason A. Ramos and Julian Smith. Jason was a rookie smokejumper in 1999. The NCSB rookies began their training in Redmond, Oregon that year. The Redmond Center had a training tower similar to, but shorter, than the current NCSB tower. Jason’s description of the exit training is included below:

The following photos show some of the exit training steps that Ramos described.

After more than a hundred of these tower jumps, the rookies were ready for the real thing.

After explaining the use of the training tower and other ground training equipment, Tobiahs led us to the Lufkin Parachute Loft. We passed the sign along the way which honored the base as the “Birthplace of Smokejumping”. The loft, built in 1939, has three main uses: 1) The parachutes are rigged, repaired and stored here; 2) Much of the smokejumpers’ jump gear and equipment is designed, made and repaired here; 3) The individual smokejumpers’ gear is stored here, ready to be donned at a moment’s notice when the siren goes off signalling a fire call.

When we entered the loft, we saw the North Cascades Smokejumper “symbol” with feathers made of used gloves, jump helmet, pulaskis and parachute pack on one wall.

A speed rack containing each smokejumpers jump gear lined one side of the loft. We learned that the on-call smokejumpers, dressed in their Nomex fire-resistant pants and shirts and their boots, remain near the loft. When the siren signals a fire call, the jumpers run to the loft and those needed for the fire call don their jumpsuits and gather the rest of their jump gear. They are trained to suit up in two minutes with the goal of the jump plane being wheels up in less than seven minutes after the siren sounds.

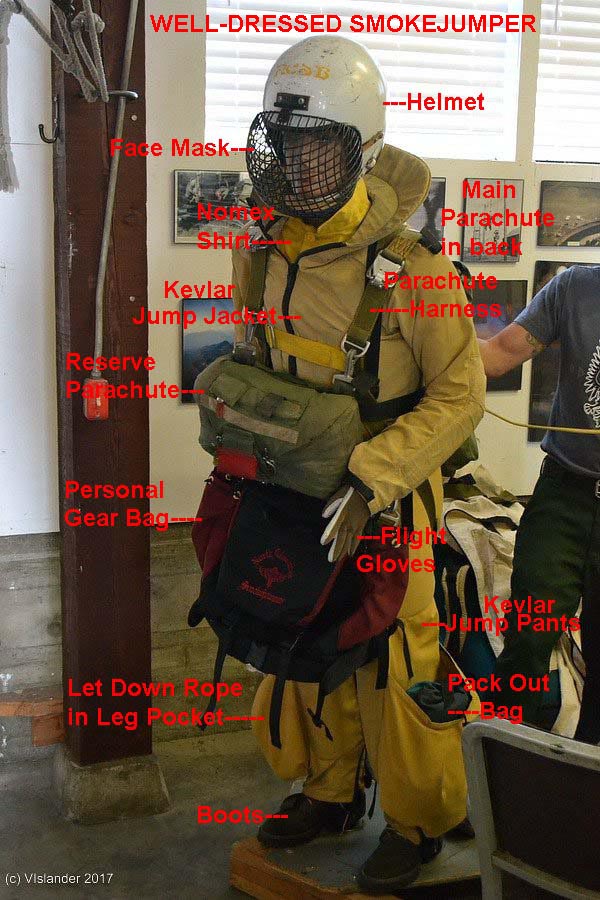

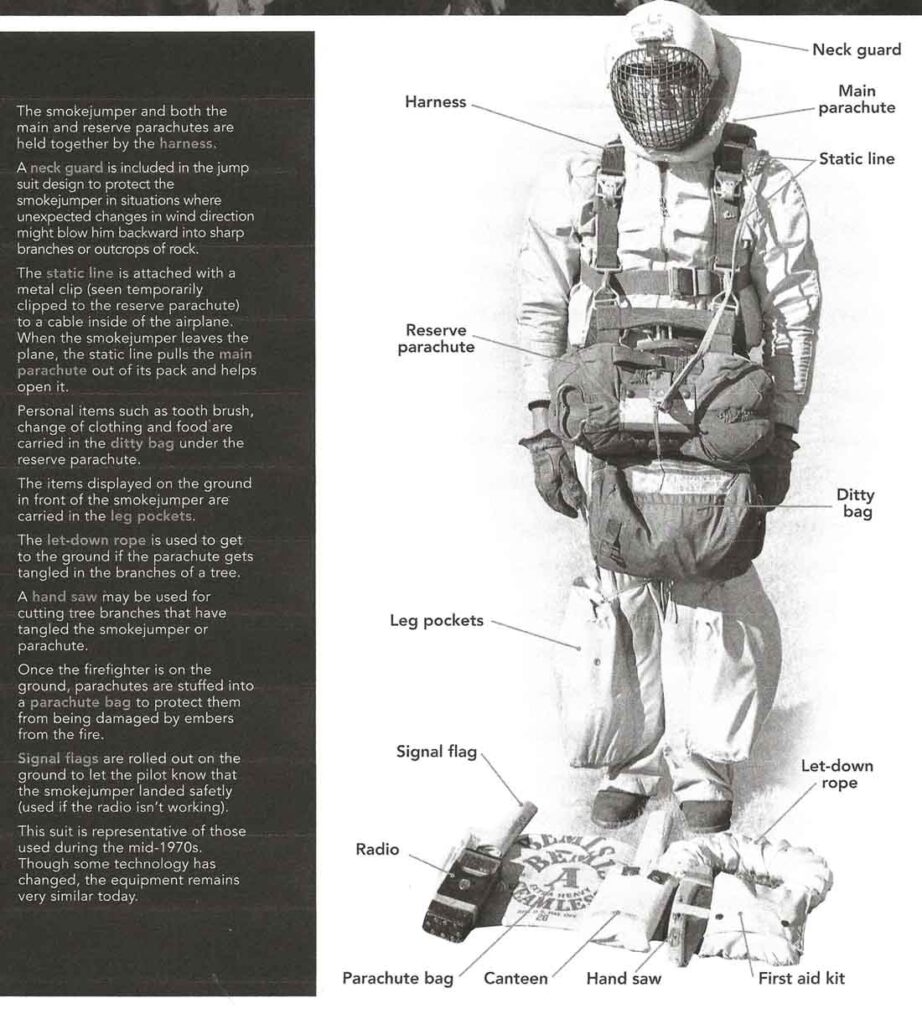

The smokejumper’s jump gear which includes the jump suit, main and reserve parachutes and harness, helmet with wire face mask, personal gear bag, let down system, hand saw or knife, ankle braces, boots and packout bag weighs between 85 and 100 pounds.

Tobiahs explained the jump jacket and pants and demonstrated suiting up. The jump suit is made of a punctureproof Kevlar fabric, similar to that used in bulletproof vests, for protection during tree and brush landings. The suit, along with their harnesses and packs, are custom designed, sewn, fitted and repaired by the smokejumpers themselves. The jacket has a high protective collar. Foam pads are held in a number of pockets which are sewn into the inside of the suit. A large pocket are added on the outside of both legs. The right leg pocket is used to hold the letdown equipment. Pockets may be added to the back of the jacket and the seat of the pants.

The jump helmet is a high-impact helmet ski helmet with a wire cage face mask to protect the jumpers eyes and face from tree branches and brush during the descent and landing. The individual smokejumpers add additional protective gear using a combination of ski, motorcycle and hockey gear.

Once the first load of jumpers are suited up, they put on their main and reserve parachutes and an equipment “Buddy” safety check is performed on all the smokejumpers. Once the plane is over the fire, an onboard spotter selects a landing spot and signals the individual jumpers when to exit the airplane. When the smokejumpers are on the ground they take off their jump suits and helmets. Fire-fighting gear including hard hats, nomex gloves, fire shelter, water and other personal gear required to support a shift of fire-fighting is removed from the personal gear bag and jump suit pockets. The jump gear and the parachutes are packed in their fire-resistant packout bags. When the jumpers (now fire-fighters) are ready, fireboxes containing fire-fighting hand tools, a sleeping bag and enough water and food for three days are dropped from the jump plane. Additional cargo boxes containing chainsaw kits and other equipment will also be dropped if needed.

When the smokejumpers are released from the fire, they assemble all of their jump and fire-fighting gear including parachutes and tools. In some cases the jumpers and all their gear can be transported by helicopter. In many cases they have to walk out to the nearest road, often off-trail, carrying all of this gear and equipment in their packout bags with a typical weight of 100 pounds or more. If the fire was in a Wilderness, this packout may take more than a day. Jason Ramos, in his book Smokejumper writes of a two mile/two hour packout in which he carried a 154.8 pound load.

In the book Just a few Jumper Stories, Rod Dow tells about what might be the packout distance record. In the early days, the jumpers often buried their garbage at the fire site before they began their packout to save weight. Then the order came down from the USFS’s national headquarters that the garbage had to be packed out. Later, two jumpers who were facing a long packout with full gear decided to bury their garbage. When they finished their 21 mile packout at the Moose Creek Ranger Station, they were greeted by the Ranger who offered to get rid of their garbage for them. Dow ends the story with Emil, the Ranger, asking ”Where’s your garbage, guys?”…Ogawa {one of the jumpers} said “We buried it.” Emil paused and then said very calmly, “I got some bad news, boys…..Go get it.” Sixty three miles over four days.”

We enjoyed the tour and the 1st hand look at the smokejumper’s life that Tobiahs gave us. We saw no evidence of the steel tower that had been moved here from Leecher Mountain and found no-one on the base who knew anything about its final fate. They suggested that Bill Moody, a long time NCSB smoke jumper during the time that the steel tower was in use and who was the NCSB Base Manager when it was replaced by the current training tower, would be the one who would be able to answer questions about the Leecher tower. Bill lived in nearby Twisp and I was given his contact information by those at the base. We called him and set up a visit.

Our visit with Bill Moody, 10/5/2023

Peggy and I visited Bill and Sandy Moody at their Bed and Breakfast in Twisp. Sandy hosts the B & B with help from Bill.

1957 was a significant year for three of us. Peggy graduated from Everett High in 1957. Two weeks after his graduation from high school in 1957, Bill started his rookie year as a U. S. Forest Service smokejumper at the NCSB. I worked the 1st, of 2, fire seasons in 1957 as a lookout-fireman for the U. S. Forest Service. These were my only two years with the Forest Service and fire fighting. On the other hand, Bill continued to work for over 60 years in fire suppression with the first 33 years as a Forest Service smokejumper. He was Base Manager for the NCSB from 1972 until his retirement from the Forest Service in 1989. After this retirement, he continued to work as an air attack supervisor and formed a consultant business which allowed him to continue contributing to advances in firefighting. He announced his retirement in 2019, but as another NCSB smokejumper who attended the NCSB 2019 reunion wrote: “He’s pretty sure he’s retired now, but with Bill, you never know”. He served on the Columbia Breaks Fire Interpretive Center Board of Directors and is still active in the National Smokejumper Association.

Bill is well known and honored in both the national and international wildfire suppression and safety world. He has been called a “legend in the smokejumping community”. One of the Smokejumper Tales in the book SPITTIN’ IN THE WIND is titled If You Don’t Know Bill, Then You’re Not A Jumper. Bill’s early contributions to international smokejumping includes training Canadian jumpers at the NCSB in 1974 and a visit to the USSR in 1976 where he made two jumps with the Russians. He then hosted the head of the USSR Aerial Fire Operations at the NCSB in 1977. He has helped advance aerial firefighting in Mongolia, Bolivia, Chile and Israel. In 2004, he began work as a consultant on modifying a 747-400 as a fire tanker capable of dropping over 19,000 gallons of fire retardant and traveled with it as it was used to fight fires in Chile, Israel and Mexico. In 2020 Bill received the Walt Darran International Aerial Firefighting Award in the category of Aerial Firefighting Safety by the Fire Aviation Working Group and the Associated aerial firefighters.

Bill and I traded knowledge and photos covering the history of both the Leecher Mountain steel tower lookout and the smokejumper training towers at the NCSB. 1957, Bill’s rookie year as a smokejumper was only three years after the Leecher Mountain steel tower was moved to the NCSB to be used in the rebuilding of the training tower there. He had received his rookie training and follow-up annual refresher training using that tower for a number of years. He was the NCSB Base Manager when the current training tower replaced the one which incorporated the Leecher steel tower in the mid 1970s. Photos comparing these two training towers appear in Bill’s book HISTORY OF THE NORTH CASCADES SMOKEJUMPER BASE .

Bill explained that the current tower was built using a steel tower obtained from the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA). The Leecher tower was completely taken apart and none of the steel from it was used in the construction of the current tower. He does not remember what was done with the Leecher tower steel, but said that it was probably recycled as scrap steel. It was not sent to another smokejumper base to be used as a training tower. It appears that the Leecher steel tower lookout, as many other Type 3 Re-Located Lookouts, no longer exists.

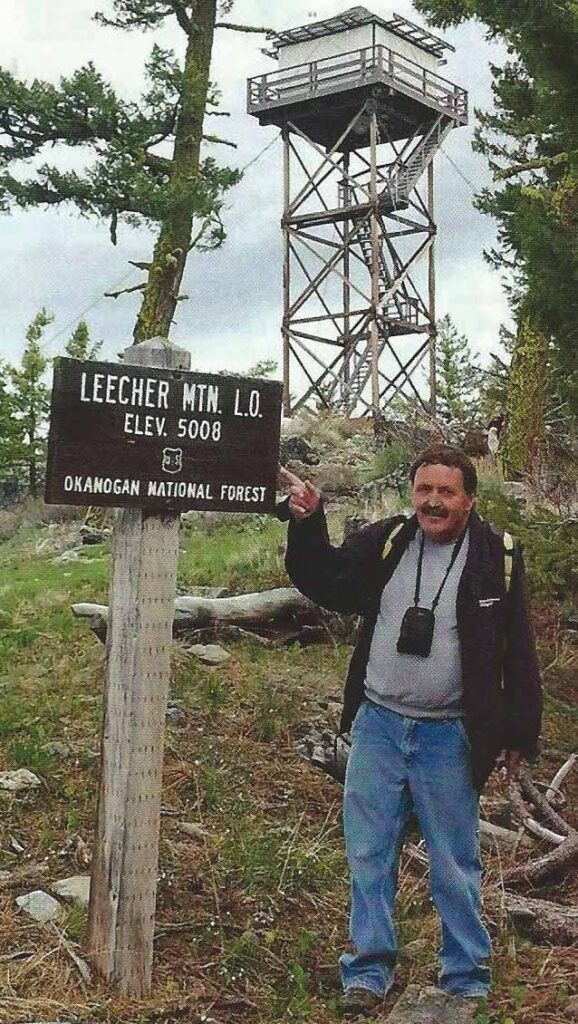

Our visits to Leecher Mountain, the ORIGIN SITE for the NCSB Smokejumper Training Tower

There have been three lookouts on Leecher Mountain. The last of these is still there and staffed, while the remains of the first is also still there. The first, which dates from as early as 1917, was a crow’s nest tree on a high point about ¼ mile from the summit of Leecher Mountain. The second was the steel tower lookout which was placed near the summit in 1922. The current Leecher Mountain Lookout, which was placed on the summit, replaced the steel tower in 1954.

Our first visit to Leecher Mountain was on June 4, 2015. We drove through burned over areas, evidence of the 2014 Carleton Complex Fire. Heavy downpours had helped douse the fire in August, 1914, but they had also caused mudslides. The lookout access road had been badly damaged by these mudslides in several places. We were able to drive to a closed gate 1.2 miles from the lookout. We walked the road from the gate through a mix of live and fire-killed trees. The lookout was not being manned. The shutters were down and the access to the catwalk was locked.

An article in the July-August, 2014 Washington Trails magazine read in part: “Lightning Bill Moves from Goat Peak to Leecher Lookout Those longing to catch a glimpse of U.S. Forest Service lookout legend “Lightning Bill” Austin will find him in a new spot this year. After a 19-year tenure at Goat peak in Mazama, Austin has been reassigned to the Leecher Mountain Lookout southeast of Twisp. The move comes amid a shrinking Forest Service budget and shifting firefighting resources……As of mid-June, Austin has settled into the Leecher Mountain Lookout and is ready for visitors.”

Then lightning started four wildfires in the Methow River Valley on July 14, 2014. They soon merged to form the huge Carleton Complex Fire which eventually burned over 256,000 acres. When the Carleton Fire spread and threatened the Leecher Mountain Lookout, Lightning Bill was forced to leave Leecher and was moved back to Goat Peak.

From washingtonlookouts.weebley.com: “July 17, 2014; The lookout was evacuated by helicopter…Flames from the Carleton Complex Fire had effectively surrounded the lookout making escape unsure at a later time. The lookout was not re-staffed as a primary lookout this season.”

When we visited the current lookout, we did not look for artifacts from the steel tower lookout. We knew from the Leecher Mountain NGS Data Sheet that the steel tower was 78.5 feet west of the center of the current tower. Comparison of a historic photo of the 1922 steel tower lookout with its L-4 ground house to our 2015 photo of the current lookout shows the relative positions of these two lookouts. The same big rocks can be seen in both photos.

We returned to Leecher Mountain on September 9, 2017 to see the remains of the Leecher Crow’s Nest. The firefighters had rescued it from the 2014 Carleton Fire. We then walked on to the Leecher Mountain summit to visit the current lookout.