Issaquah Alps Trails Club (IATC) HISTORY:

In 1976, Harvey Manning, a noted local hiking guidebook author and ecologist began a revolution ~ “throw off the wheels that bind, get out of your cars and walk, walk, walk”.

He highlighted a small cluster of forested and undeveloped low “mountains”s east of Seattle and pushed them as the center for his get out of the car and walk campaign. He invented the catchy name, the Issaquah Alps, for the area. Harvey pointed out that people should not only hike in the nearby Issaquah Alps, but that they should leave their cars at home and ride the bus to the trailhead. At that time the bus line from Seattle to Issaquah was the Metro 210. Harvey came up with the campaign slogan “Leave your cars at home and hike in the “Wilderness on the Metro 210”.

A group of like-minded fellow hiking enthusiasts joined Harvey in his campaign. In 1979, this core group agreed to lead a series of spring hikes into the Issaquah Alps for Issaquah Parks. During a May 5, 1979 hike, the group of hikers was asked while stopped atop Long View Peak “Would you like to organize?” So was born the Issaquah Alps Trails Club. The club’s first meeting was held on May 19, 1979. AS the club’s guidelines and objectives were formulated it became obvious that since most of the Alp’s lands were privately owned and were under development pressure that these wooded wildland could disappear over time unless more of the property could be owned by the public. This led to the conclusion that the IATC would need to become involved in the land use politics of the region. The club set up an active hiking program to introduce the public to the Issaquah Alps. The hiking program, from the beginning, was meant to be an integral part of the politics of public land acquisition and land use planning of the Issaquah Alps. It was believed that if we put a pair of boots on the trail, then the owner of those boots would become a voter to save that trail. The new campaign slogan became “Boots on the Trail Equals Votes for the Trail.” Four hikes were led by the club on the weekends as well as a Wednesday evening hik. Hikers met in Issaquah, “The Trailhead City”, and were then led by the IATC’s volunteer hike leaders up to the volunteer built trails on Squak, Tiger and Cougar Mountains which surounded Issaquah.

Cougar Mountain Regional Wildland Park (CMRWP) History

Cougar Mountain was a key area for the “saving of the Alps”. In 1980, 2 small ex-Nike missile sites and a small block of public school land grant property managed by the DNR were the only publically owned property on Cougar Mountain. Much of the other property was owned by the Palmer Coking Coal company, based in black Diamond, which had bought the land from the Pacific Coast Coal Company. There were several competing groups with competing plans for Cougar Mountain’s future. In 1980, the IATC announced their proposal for the future use of the 2000 acre wilderness atop Cougar Mountain in a news release signed by Barbara Johnson, the Founding vice-President of the IATC. The IATC’s proposal would result in King County acquiring the plan to create a King County Park. The club stated that “it envisions a forested area that is in a basin ringed by half a dozen peaks that make up Cougar Mt. The park would be be for hiking, backpacking and horseback riding where practical. There are four geographic entities in the proposed area, anyone of them is suitable as a local paek. But if all four are preserved, they become a large enough wilderness to be worthwhile to come from Seattle; thus , truly a regional park….Over 1000 people have walked the trails of the Issaquah Alps through the auspices of the club. Hikes range from toddler walks to strenuous 10-20 mile marches. Most of them are arranged around the Metro 210 schedule, and car pools to the trailheads are formed at the bus stops….All hikes are free, the leaders volunteer their time and knowledge…..Often the complaint is voiced that wilderness parks are far away, and only the rich can use them, or only the young…This proposed park is in an urban area already served by Metro bus. The footpaths, today are usable by those of all ages, abilities and income levels….The Issaquah Alps Trails Club feels the time is right to preserve this lovely urban wilderness for all people in the region.”

In 1979, the King County Council began a study program aimed at updating the future land use plans and zoning for King County. The Council formed citizen-based committees in many areas of the county to help in this task. The Newcastle Community Plan Committee was formed and given the task to formulate recommendations to the County Council concerning the future zoning and land use plans of this area which included Cougar Mountain. The 20-member committee included 10 local community members and ten representatives of development organizations. The IATC presented their Cougar Mountain Park proposal to this committee in January, 1980. Many on the committee agreed that the IATC’s park plan was a good idea.

There were several competing groups with competing plans for Cougar Mountain’s future. In August, 1980, an article appeared in the Journal American, a Bellevue newspaper, with the headline “Four urban villlages for 44,000 residents proposed high atop Cougar Mountain”, The article explained that the plans of the Central Newcastle Property Owners association, which represented property owners, developers and investors, would reach their full development by 1995. A few on the committee favored the developer’s plans.

The committee’s report June, 1981 report to the County Council contained recommendations both for a County Park and more development on Cougar Mountain. The County Council’s Ordnance 6235 which amended the Newcastle Area Zoning Guidelines was passed by the Council on December 20, 1982, but was then vetoed by Randy Revelle, the King county Executive on January 6, 1983. Revelle explained that he vetoed the bill due to its lack of a firm commitment to the proposed CMRWP and because it encouraged unnecessary development in an area unsuited for major growth. It took more negotiating within the Council, before an acceptable re-written ordnance was presented to the county Executive. Revelle signed the re-written ordnance at the Return to Newcastle celebration put on by the IATC on June 5, 1983. This was the official start of the CMRWP.

Trails and the IATC:

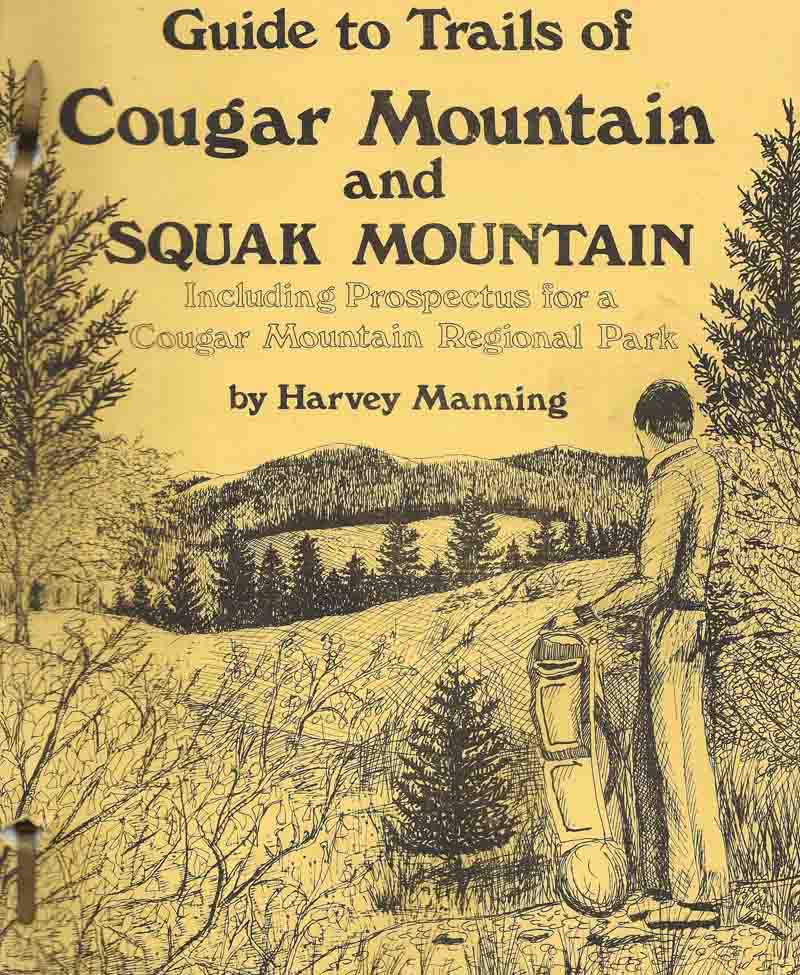

The CMRWP was now official and growing in size, but there was not an official hiking trail system. From the beginning, the hikes that the IATC led on Cougar Mountain were on routes and trails planned and built by volunteer IATC members. In large part, the routes used on Cougar Mountain used remnants of the past years of mining and logging. There were a few old roads which had been used as haul roads to carry coal and logs to the market and to mills.There were bulldozer built trenches cut in an attempt to find new coal and fire clay seams. In addition horse and buggy roads and trails had been used by miners and loggers to get from their nearby farms and homes to their work stations at the coal mines and logging stands. Remains of old logging and mine company railroads also existed. The IATC published Harvey Manning’s 1st edition of the Guide to Trails of Cougar Mountain and Squak Mountain. in March, 1981. This guide contained a description of the club’s volunteer built trail system as well as an impassioned plea for the club’s proposed Cougar Mountain Regional Park and an argument for the park rather than the developer’s proposed large scale development.

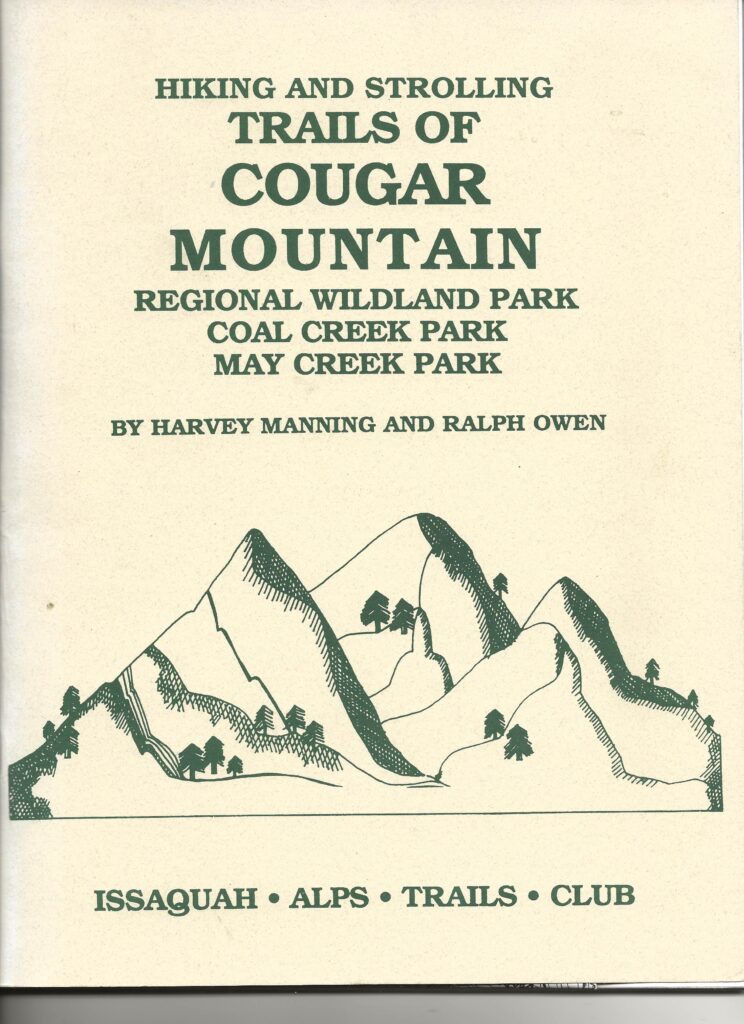

/The similarly named Blackwater Trail and Blackwater Connector Trail are good examples of IATC trails which used existing routes on Cougar Mountain. The Blackwater Trail was designed by Harvey as the most direct route for hikes between the Claypit and Wilderness Peak ( the high point of Cougar Mountain) through what he called The Wilderness. The Mutual Materials company had been mining fire clay from the Clay Pit since the 1950s. The clay was being used in the manufacture of bricks at the brick plant in Newcastle. There was always a concern that they might run out of clay. Trenches had been bulldozed south from the claypit into the Wilderness in an attempt to find new clay deposits. Harvey had used these trenches as the route for his trail which led along the bottom and along the edges of the trenches. Harvey’s description of the Blackwater Trail which is contained in the followup Cougar Mountain guidebook, Hiking and Strolling Trails of Cougar Mountain Regional Wildland Park.

Harvey called the maze of trees, brush and swamps on the eastern edges of Cougar’s highlands, The Wilderness. His description of The Wilderness from the same guidebook is included below:

Harvey uses the term wilderness many times when writing about the Wildland Park. The U. S. Congress wrote the legal definition of wilderness in The National Wilderness Act of 1964. This definition was to be used by Congress when designating a new Federal Wilderness and was meant to providemanagement guidance for the U>S> Forest Service and National Park Service managers of those Federal Wildlands. This definition includes “A wilderness in contrast with those areaswhere man and his works dominate the landscape is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” The Act also gives Further examples of criteria that define an area as a wilderness including:

o Minimal Human imprint

o Have no commercial enterprise within them or any motorized travel or other form of mechanical transport.

The forested lands on Cougar Mountain do not meet this legal definition of wilderness. There were several coal minimg oprations on Cougar from 1860s until the 1960s. The Mutual Materials Company was still extracting fire clay from the claypit and the road used to haul truck loads of clay to their Newcastle brick plant was still in use. Traces of other roads and railroad grades, which ha been used to haul coal from the mines to docks in Seattle and logs to mills in Necastle, where timbering was cut to shore up the mines and lumber was cu to be used in constructing housing for the miners. Logs were hauled to Washington Lumber and Spar compamy’s railroad to their large sawmill in Kenneydale which stood where the Seahawks training facilities now stand. A better term for the Cougar park was wildland. It certainly was wild enough so that experienced hikers and outdoor persons could still become lost. Another good description would be one that Harvey often used; a wildland that nature is turning back into wilderness.

Harvey uses the term wilderness many times when writing about the Wildland Park. The U. S. Congress wrote the legal definition of wilderness in The National Wilderness Act of 1964. This definition was to be used by Congress when designating a new Federal Wilderness and was meant to providemanagement guidance for the U>S> Forest Service and National Park Service managers of those Federal Wildlands. This definition includes “A wilderness in contrast with those areaswhere man and his works dominate the landscape is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” The Act also gives Further examples of criteria that define an area as a wilderness including:

o Minimal Human imprint

o Have no commercial enterprise within them or any motorized travel or other form of mechanical transport.

The forested lands on Cougar Mountain do not meet this legal definition of wilderness. There were several coal minimg operations on Cougar from 1860s until the 1960s. The Mutual Materials Company was still extracting fire clay from the claypit and the road used to haul truck loads of clay to their Newcastle brick plant was still in use. Traces of other roads and railroad grades, which ha been used to haul coal from the mines to docks in Seattle and logs to mills in Nwcastle, where timbering was cut to shore up the mines and lumber was cut to be used in constructing housing for the miners. Logs were hauled to Washington Lumber and Spar compamy’s railroad to their large sawmill in Kenneydale which stood where the Seahawks training facilities now stand. A better term for the Cougar park was wildland. It certainly was wild enough so that experienced hikers and outdoor persons could still become lost. Another good description would be one that Harvey often used; a wildland that nature is turning back into wilderness.

/

In the Mid-1980s, Jim Cadigan and I both decided to Create an alternative to the Blackwater Trail route between the Claypit and Wilderness Peak. We took turns flagging and clearing a route through the brush and vine maple between the East Fork Trail and the south end of the Blackwater Trail. We called the new route the Blackwater Connector Trail. The new alternate route for the hike between the Claypit and Wilderness Peak started at the Claypit, then and cut past Jerry’s Duck Pond onto the East Fork Trail which was followed to the Blackwater Connector Trail. This was then followed through the brush to the Blackwater Trail which was then followed up to the Wilderness Peak summit. This route is the one followed by the Pee and Repeat Trailmix group , in reverse, on their January 30, tour de force Cougar Mountain Traverse.

Harvey Manning began leading a Cougar Mountain Grand Tour hike which he named The Cougar Ring for the IATC in early 1980. This 12 mile -full day hike was designed to introduce the public to the delights of the club’s proposed park. The hike announcement in the IATC Alpiner for one of his first Cougar Ring hike read:

COUGAR MOUNTAIN RING TRAIL. Tuesday, March 18, 1980. Meeting place, Isaaquah Park I, Ride, Leader: Harvey Manning, 746-1017 This hike explores the centerpiece of our proposed Cougar Mountain Regional Park. This is a full day, 12 mile hike following old wood roads, bear trails, and red ribbons- visiting the Long Marsh, Far Country, the Wilderness, the High Marsh, with great views. The Cougar Mountain Ring was led by Harvey and other IATC volunteer hike leaders at least once a quarter for the next 10 years. The hike began at the Coal Creek Townsite Trailhead (AKA the Redtown Trailhead) on the west edge of the park, visited the Wilderness and Wilderness Peak before descending to the Wilderness Creek Trailhead on the Renton-Issaquah Road via the Wilderness Cliffs Trail (now known as the Jim Whittaker WildernessPeak Trail.) .) The hike was led on IATC built trails and each leader picked their own exact routing. The “official” routing between the Claypit and Wilderness Peak followed Harvey’s Blackwater Trail past the Blackwater Pond. MY first hike on the blackwater Trail was with Harvey when he led he Cougar Mountain Ring on May 26, 1980. The first time that I led a hike on the Blackwater Trail was on the first hike that I led for the IATC, a Cougar Ring hike on Sunday, April 5, 1981.

King County Parks takes over management of the CMRWP and its trail system.

After the creation of the CMRWP became official King County policy, King County Parks was given the task of designing and managing a wildland park and were alloted funds to peform that task. This presented a new challenge to the ball-park, picnic-table park managers within KC Parks. In 1989, KC Parks began working up a formal trail plan. At that time, the only trail system was that built and maintained by the volunteers of the iATC. Members of a park trail crew, who had training in designing building and maintaining wildland trails were hired. The trails that were to be on the park’s trail system were selected and new trail signs and maps were prepared. Many of the routes pioneered by the IATC were rebuilt on gentler and more maintainable grades. New trails were built by the new park trail crew. Trail maintenance was then taken over by the KC park crew. Some of the IATC’s routes, including both the Blackwater Trail and the Blackwater Connector Trail, were abandoned. Access to these trails was cut off, existing trail signs were removed and these routes were not included on any of the new King County Park maps. A committee consisting of local residents, including members of the IATC, was formed to work with KC Parks to formulate a master plan for the CMRWP. One of the points to come out of this committee was that the eastern slopes of Cougar and the Wilderness Section were to be managed to support wildlife as a priority over recreation. Many of the trail replacements were done to support this priority. The map contained within the current CWRWP online brochure contains this note “Habitat Conservation Area:” Park development and trails have been excluded to protect threatened wildlife. Please help nature’s recovery by staying out of this section of the park.. My last hike on the Blackwater Trail was after it was abandoned by the KC Parks crews.

Fine grained fireclays developed on Cougar mountain along with the coal seams. Bellevue based Mutual Materials operated the clay pit on cougar mountain, starting in th late 1950s. The clay was used in its Newcastle brick plant near Coal Creek parkway in Newcastle. The plant supplied bricks for both Red Square on the UW campus and for Safeco field. When we first began hiking in this area on Cougar we could see the brightly colored cream, yellow and red clays in the pit. These colored clays reminded us of the brightly colored sandstones of the National Parks of Utah and the SouthWest. When the brightly colored fireclays had all been extracted, gray colored clays remained in the pit. The clay was dug from the bottom of the pit by a bull dozer. The dozer operator formed mounds of clay Which allowed the clays to dry. When the brick plant needed more clay and the clay in the mounds were dry, large trucks were driven up from Newcastle, loaded with dry clay and then hauled truck load after truckload of clay to the brick plant.This resulted in heavy truck traffic on the Claypit Road and other roads in the area for two weeks. This happened several time each summer. This operation resulted in the clay pit increasing in depth and over-all size. The claypit was known by many as the hole in the doughnut. The CRWP surrounded the claypit and the park was the doughnut and the claypit was the hole in the doughnut.The dozer was also used to cut exploration trenches south of the claypit in an attempt to find more clay in case they ran out of usable clay in the claypit. Trails, including the Blackwater Trail, were built using the trenches directly south of the claypit. Additional trenches were cut along the south edge of the East Fork Trail. These were not used for trails as they were left full of brush and downed trees.

On February 23, 1999,King County Exeutive Ron Simms announced that the county had purchased the clay pit. The purchase agreement contained the stipulation that mutual materials could continue extraxting clay until 2040 under a lease. Mutual Materials were considering closing their Newcastle brick plant, both because of the scarcity of suitable clay and because he brick market and brick prices were fslling due to the continuing depression. In August 3,2012, Mutual Materials announced that the company was putting the brick plant on the market and that they were working with developers on a plan to place homes and apartments on the brick plant property. All mining was ceased at the claypit due to these changes.