REGIONS: ORIGIN SITE ~ North Central WA, RE-LO SITE ~ North Central WA

I wish to thank Rex Kamstra and Eric Willhite for sharing the results of their expert research with me.

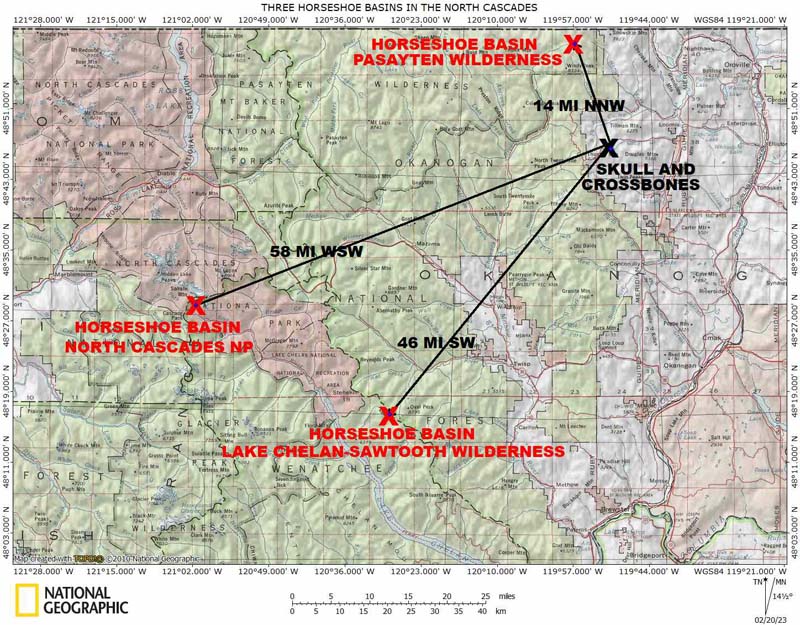

The move of the Skull and Crossbones Lookout L-4 cab to Horseshoe Basin in the Pasayten area of the North Cascades Primitive Area in 1953 is an unusual example of a Type 2 Re-Location. The U.S. Forest Service’s lookout was sold to a private individual and then was moved onto the Okanogan National Forest’s North Cascades Primitive Area for the use of the new owner who held a sheep grazing permit there. This grazing permit continued after the area became the Pasayten Wilderness in 1968 under the special provisions of the 1964 National Wilderness Act. The cab was reported to still exist in 1968, but evidently it was destroyed in 1972. The history of the re-located lookout and its use is also interesting as it reflects the nation’s changing ideas concerning the best use of the publicly owned forests and grasslands, the difference between the Forest Service’s and the National Park Service’s public land use management policies and the long battle over the creation of a North Cascades National Park.

Who Bought the Skull and Crossbones Lookout and Which Horseshoe Basin Was it Moved To?

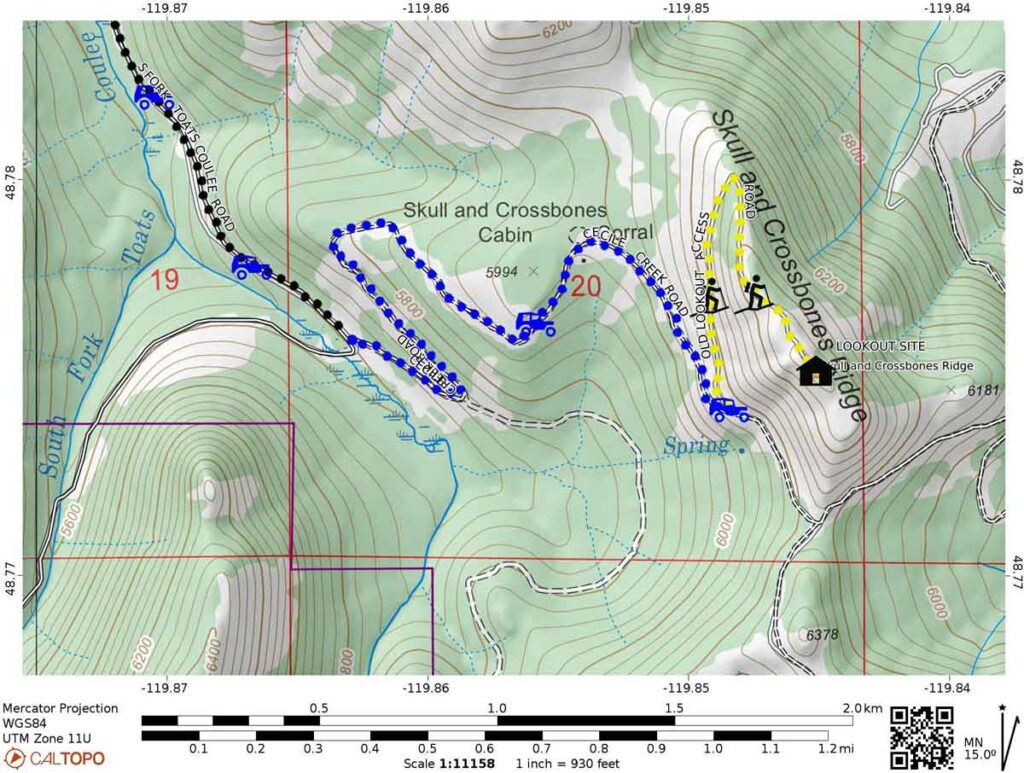

A ground mounted L-4 lookout was built by the Forest Service 10 miles WSW of Loomis on the Skull and Crossbones Ridge. According to several sources, the Skull and Crossbones Ridge was the site of a short battle between sheepherders and cattlemen in the early 1900s. The name was derived from cattlemen placing skulls and crossbones of sheep there as a warning to sheepmen.

The references differ on the construction date, but the most definitive date of 1932 comes from a newspaper article that Ron Kemnow has in his website washingtonlookouts.weebly.com: “August 15, 1932: Having completed construction of a number of lookout houses, including one on Skull and Crossbones above Loomis, E.W. Allen and Raymond Johnson are spending a few days in town. (The Wenatchee Daily World)“

The Skull and Crossbones Lookout entry in Ray Kresek’s 3rd edition of FIRE LOOKOUTS OF WASHINGTON reads in part: “ Was sold to a sheep rancher and moved by helicopter to Horseshoe Basin in 1953.” No additional information concerning the exact location of the move or the identity of the sheep rancher was given in Ray Kresek’s book or the other references usually used by “Lookout Chasers”. These references do not explain which of several Horseshoe Basins in Washington the cab had been moved to. There are three Horseshoe Basins in the North Cascades and they were all within the Okanogan National Forest at the time of the move. Today, two are in Forest Service managed wildernesses and one is within the North Cascades National Park. The closest and most likely Horseshoe Basin is the one in the Pasayten Wilderness.

Hikers, conservationists and employees of the U. S. Forest Service all knew which Horseshoe Basin it was. They also knew the name of the sheep rancher. Harvey Manning wrote in the October-November 1968 Wild Cascades, the Journal of the North Cascades Conservation Council,: “Mr. Smith,…with FS approval,…picks up a lookout cabin…and moves it to a knoll beside his airport, a lovely meadow only 4 ½ miles from the road end at Iron Gate Camp”.

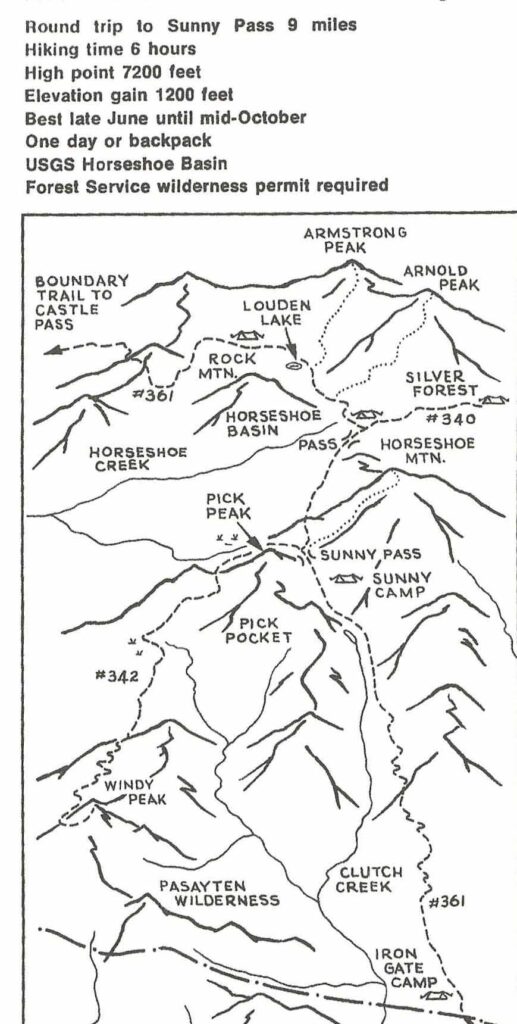

This description closely matches the description written by Harvey Manning for the hike to the Horseshoe Basin in the Pasayten Wilderness in his 1970 guide book 101 Hikes in the North Cascades. There, he describes the 9 mile round-trip hike from Iron Gate to Sunny Pass, the entrance to the Horseshoe Basin. At Sunny Pass, he writes…”be prepared to gasp and rave. All around spreads the enormous meadowland of Horseshoe Basin…”

More details of the story are given in a pair of July, 1968 letters included in the same issue of The Wild Cascades. Harvey Manning wrote the first, as Editor of the Wild Cascades, to the Supervisor of the Okanagan NF asking several questions about the Forest Service’s management of Horseshoe Basin. Answers to these questions were provided in the return letter signed by Forest Supervisor Don E. Campbell:

Question #1: “In Horseshoe Basin there is a cabin, marked US Government Property. All the evidence indicates that this is used by a private party who grazes cattle in the basin. Was the Cabin built by the Forest Service? For what Purpose? Is it used by the Forest Service? Or by the holder of the grazing permit?”

Answer #1: “The cabin, in Horseshoe Basin, to which you referred, is an old lookout house which was moved from the high point, where it used to serve to its present location. It was moved under permit by the grazing permittee and is used exclusively by Emmet Smith, the permittee , for the administration of his grazing allotment.”

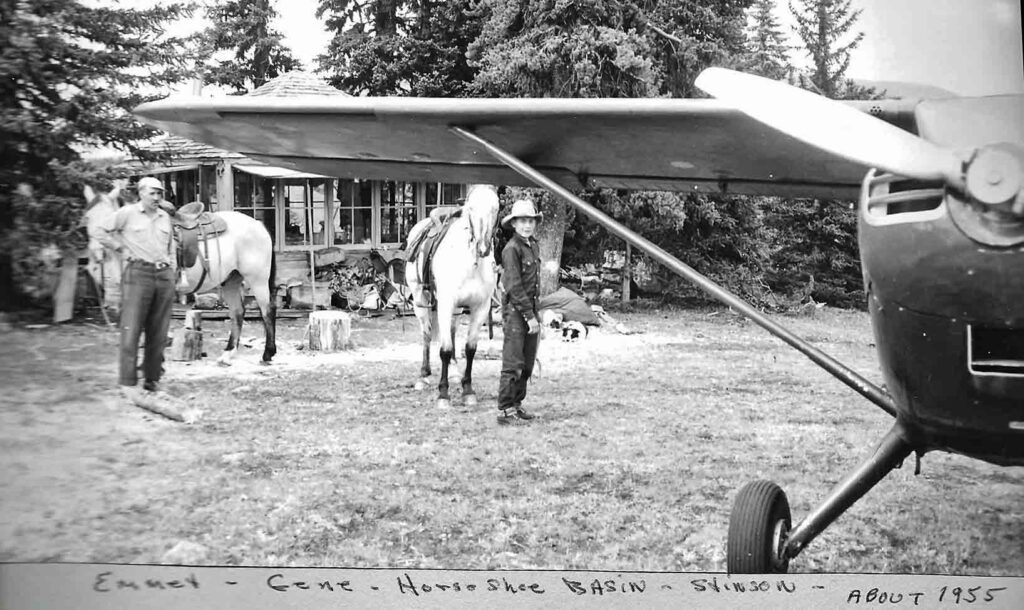

Harvey also asked “how long has Mr. Emmet Smith (and his family) held the grazing permit in Horseshoe Basin?” Don Campbell answered “Mr. Smith’s father was issued a sheep permit which included Horseshoe Basin in 1917. The permit went to his sons in 1938. The permit was recently converted from sheep to cattle.” He also reported that Emmet Smith’s permit was one of six grazing permits existing in 1968 in the North Cascades Primitive Area.

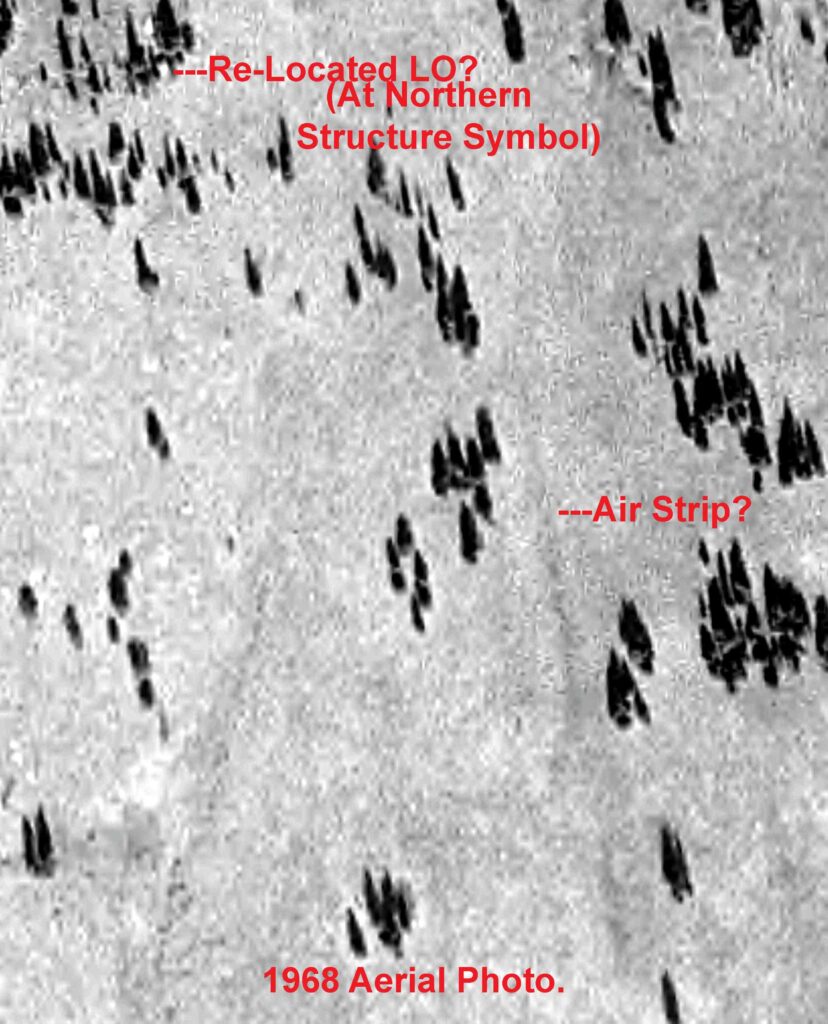

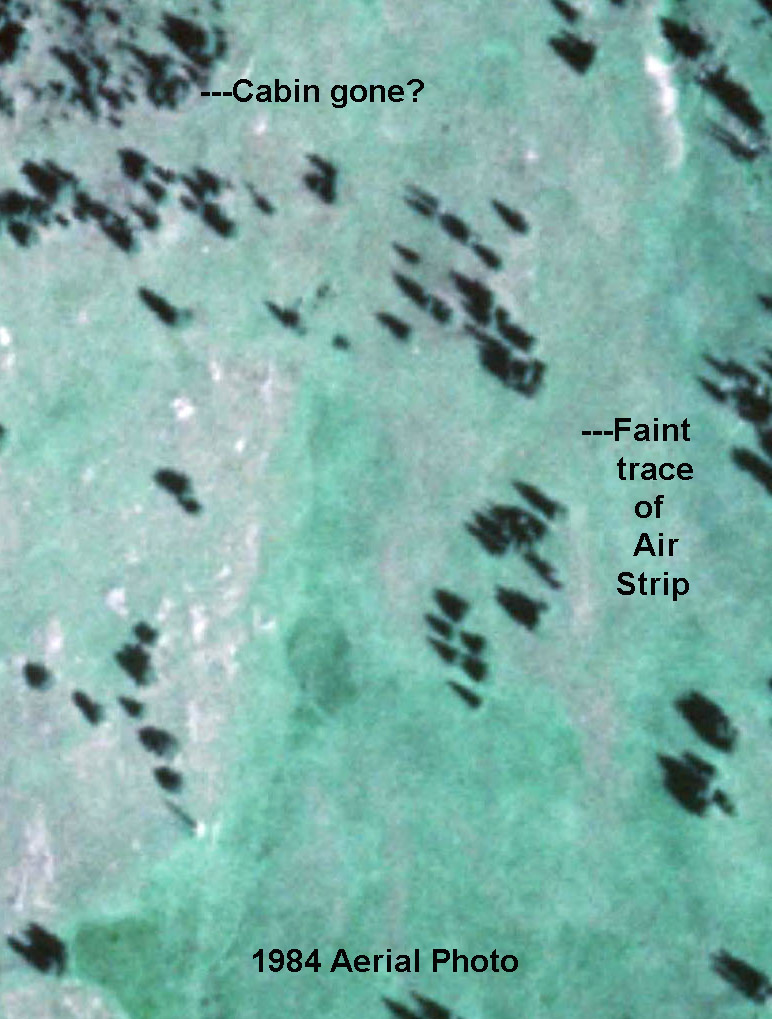

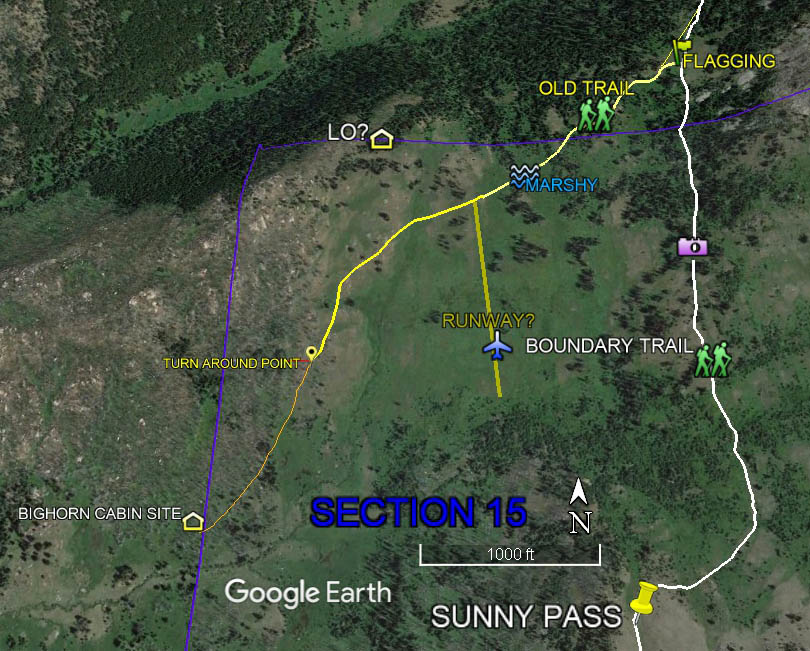

Harvey also asked the Okanogan NF Supervisor about the airplane landing strip in Horseshoe Basin which he said was in the meadow adjacent to the cabin. Harvey described the meadow as “ditched for drainage, staked for boundaries and marked by an air-sock pole”. Don Campbell answered that the landing strip was “used exclusively by the grazing permittee”. He also wrote that “use of this landing strip was established before the area was designated as a Primitive Area and has been allowed to continue under that principle”. If Campbell is correct, then the air strip was first used in the early 1930s as the Whatcom Primitive Area was designated in 1931 and then enlarged and renamed the North Cascade Primitive Area in 1935. The exclusive usage is confirmed by the Washington Pilot’s Guide. The 1966 edition of this guide lists over 180 airports in the state including commercial, municipal, private and emergency fields available for public use. The air strip in Horseshoe Basin is not listed in the guide. It also does not show on the 1968 Kootenai Sectional aeronautical chart.

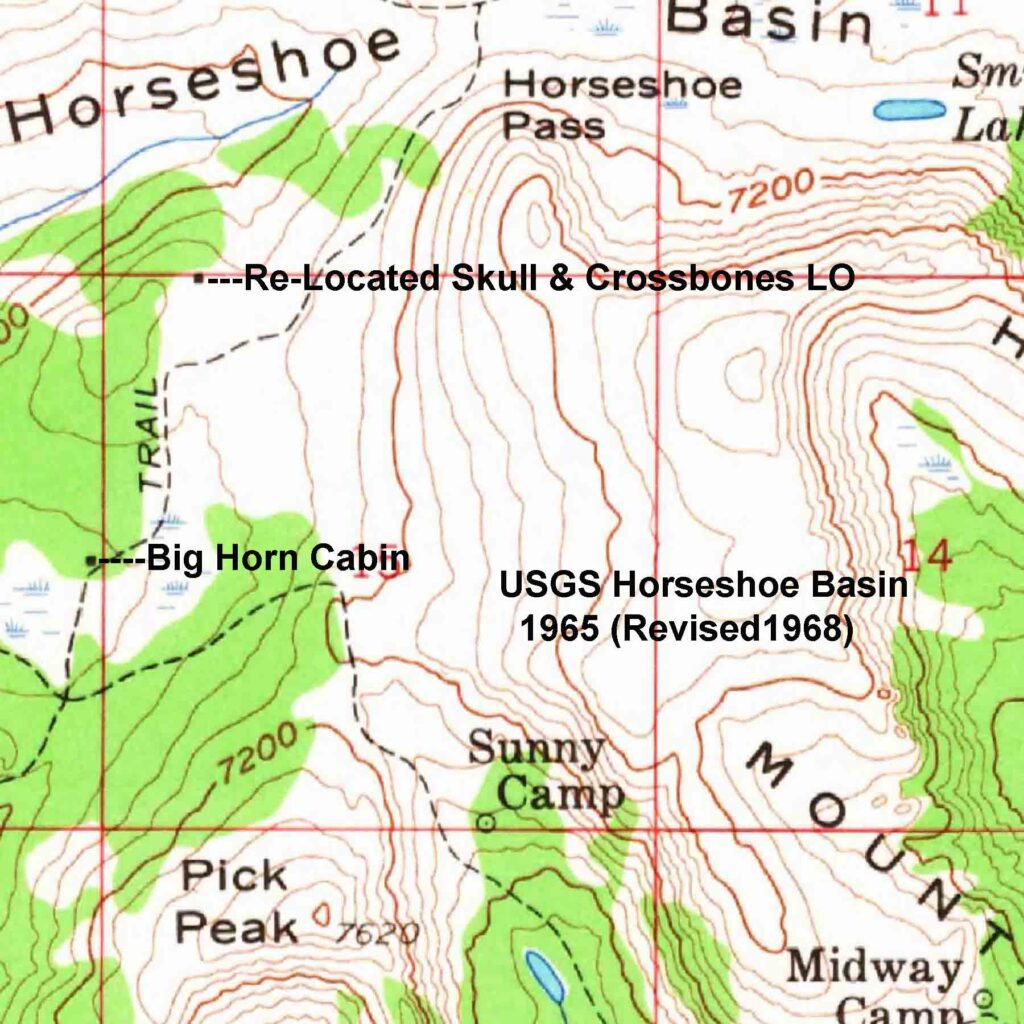

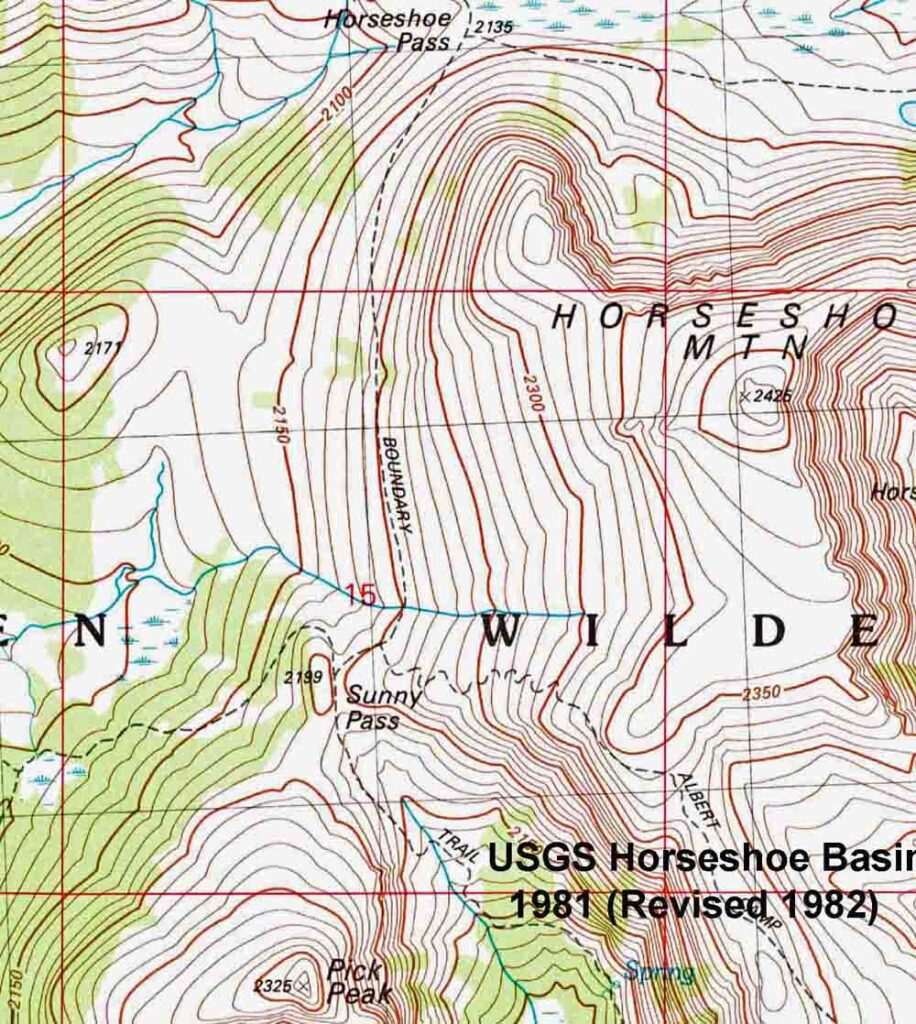

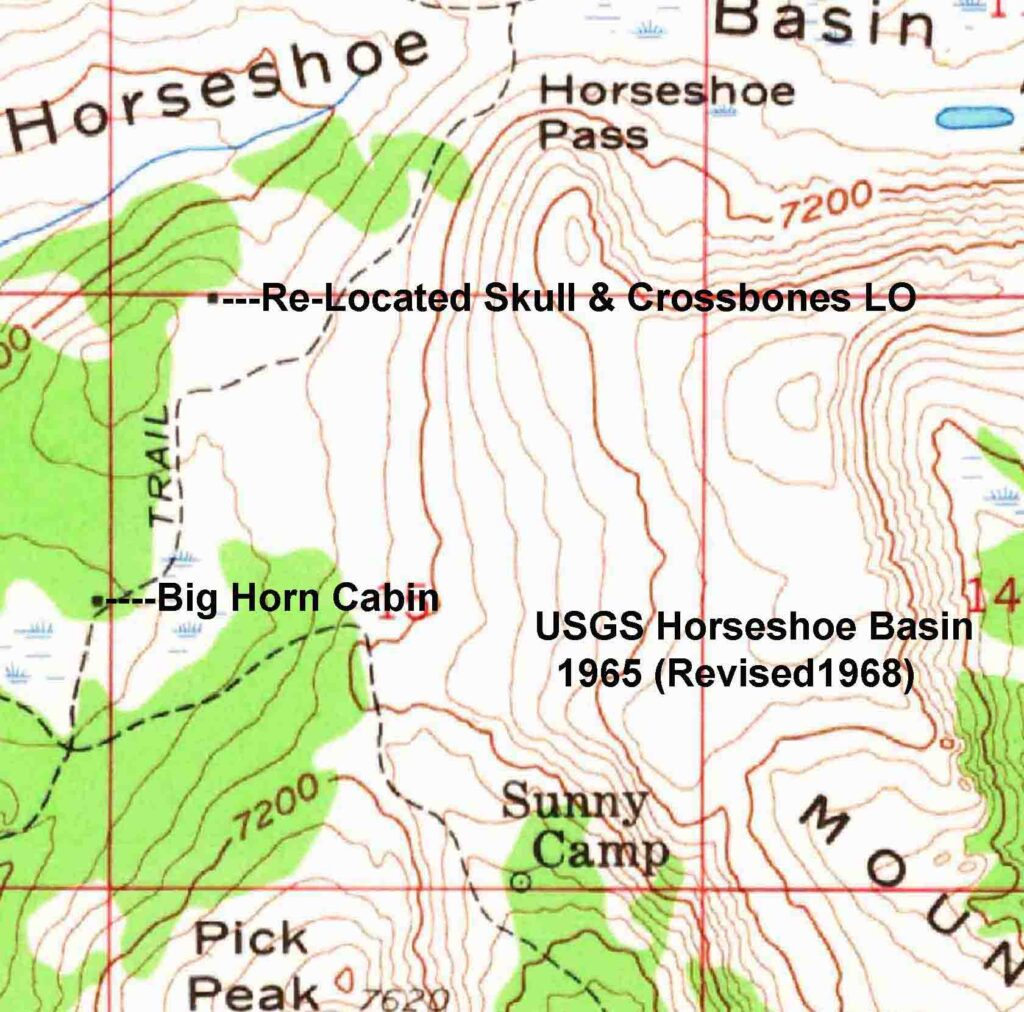

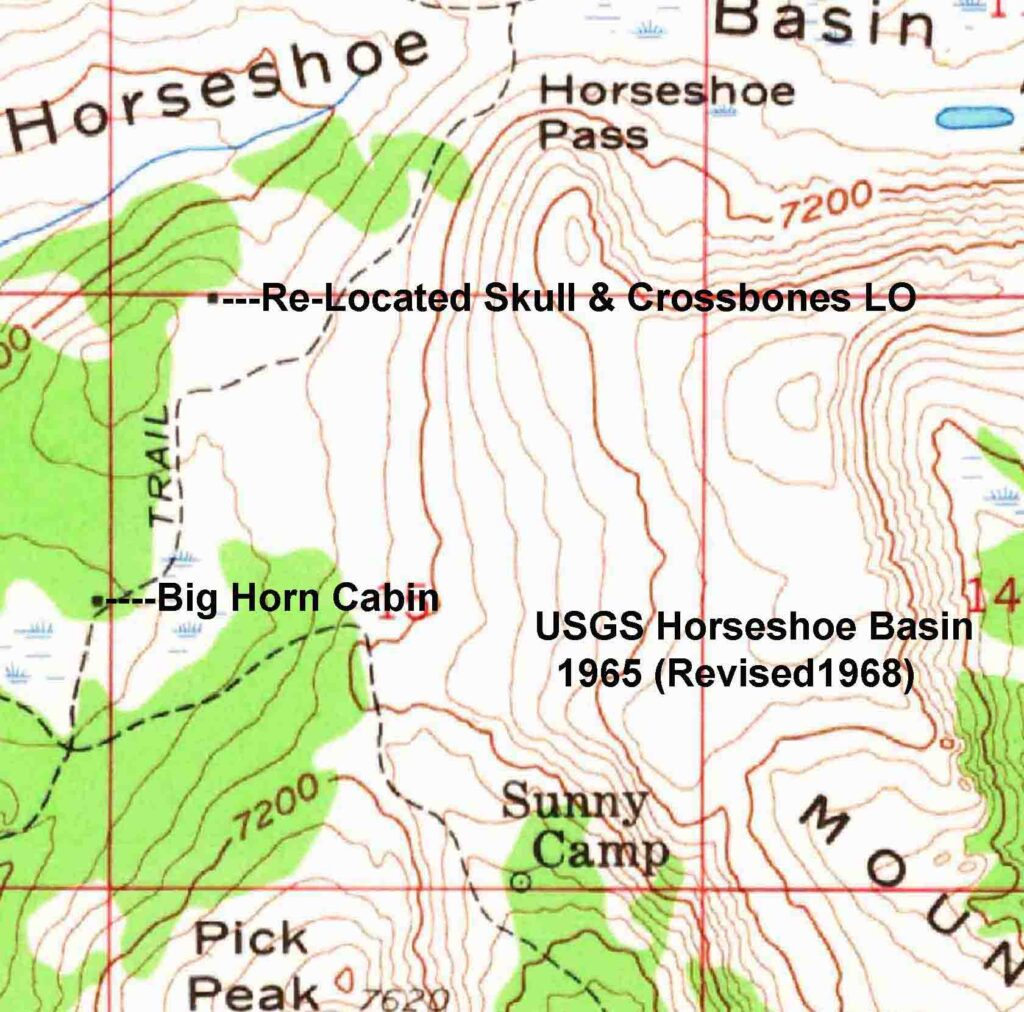

Where in the Horseshoe Basin was the relocated lookout placed? A 1968 USGS map has two symbols indicating structures in Horseshoe Basin. Both of these buildings were used by the Smith family in the administration of their grazing allotment.

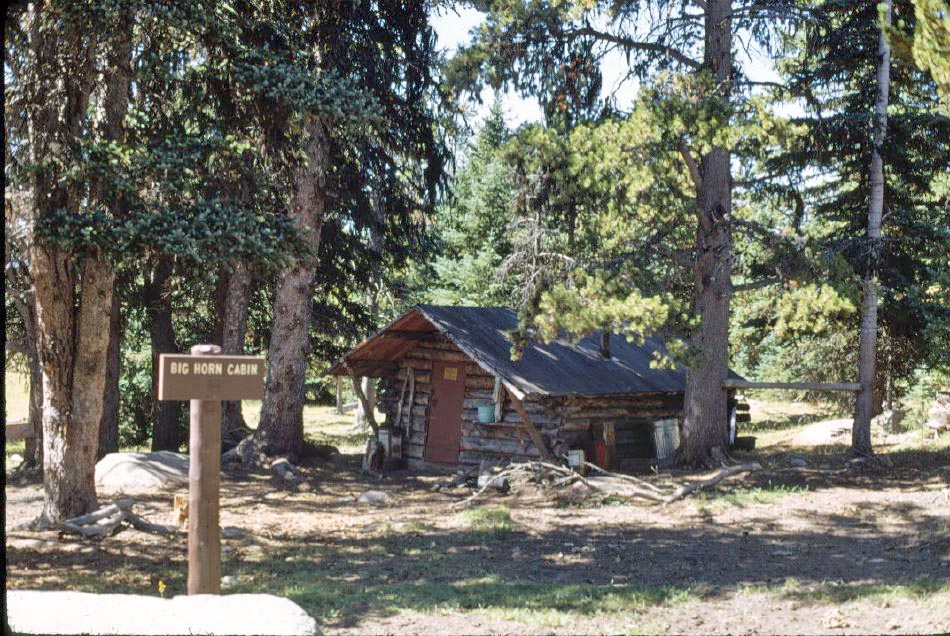

The structure indicated near the west boundary of Section 15 was the Big Horn Cabin.

The Historical Society’s description reads in part: “ The Big Horn Cabin was built by the Smith family in 1932 for their sheepherders to utilize while in Horseshoe Basin…In 1933, the Forest Service locked the cabin up and took possession of it for their use. The Forest Service subsequently agreed to share the cabin with the Smith family since they had the grazing permit for the area to justify use. The Smith Family continued to use the cabin until they moved the Skull and Crossbones Lookout Cabin into Horseshoe Basin for range use in 1952 {sic}. The cabin is on…the 1956 USGS map close to N 48o57.883’ W 119o 57.009’…The cabin was retained in the wilderness for administrative use by the Forest Service until it burned in the 2006 Tripod fire.”

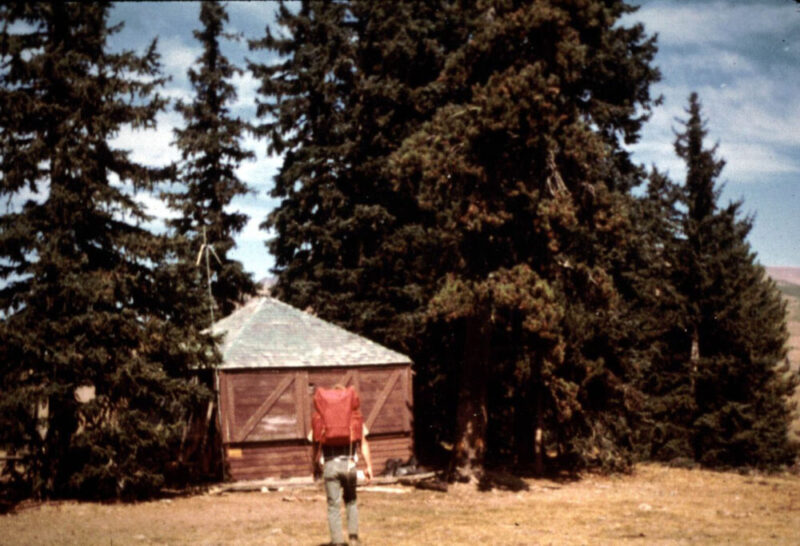

The descriptions of the re-located lookout’s location places it near the air strip and the photos show it to be in a grove of trees. A 1968 aerial photo appears to show a building in a grove of trees at the site of the map’s northern structure symbol with the air strip nearby.

In 1935 the USFS designated 801,000 acres of the Okanogan and Mt. Baker National Forests, including Horseshoe Basin, as the North Cascades Primitive Area. New livestock grazing permits were not allowed, but pre-existing ones such as the Smith’s Horseshoe Basin grazing allotments were continued under a “grandfather” clause.

In 1968, after nearly 75 years of National Park proposals and counter-proposals, the US Congress passed the act creating the North Cascades National Park and the Pasayten Wilderness. Much of the North Cascades Primitive Area was transferred from the USFS to the National Park Service to form the new national park. The rest of the North Cascades Primitive Area to the east of the new national Park was designated as the Pasayten Wilderness. This new wilderness, which included the Horseshoe Basin, was to be managed by the USFS. The 1964 Wilderness Act prohibited livestock grazing in areas designated by the US Congress as wilderness. The Act contains a Special Conditions section which allowed grazing permits in place at the time of the wilderness designation to remain in place. Emmet Smith’s livestock grazing permit, which had been converted from sheep to cattle in 1965, was allowed under this Special Condition.

The USFS’s 1973 Pasayten Wilderness Plan stated there were 49 cabins, built mainly by miners, trappers, grazers and fire lookouts built by the USFS still in the wilderness. The plan was to remove the three existing Stockmen’s cabins by 1978. While the Horseshoe Basin L-4 cab is not specifically listed as one of these three, the structure which was seen on the 1968 aerial photo, cannot be seen in this same location on a 1984 aerial photo or in a 2017 Google Earth image.

The re-located Skull and Crossbones Lookout was apparently destroyed by the USFS in 1972. The following comment by a retired wilderness ranger, which was contained in a WTA trip report, provides a clue about the final fate of the re-located Skull and Crossbones Lookout: “Interesting, I was also a wilderness ranger there in 1973-1976 based out of Horseshoe Basin. There at first were 2 cabins there. I was out of a cabin that was signed Bighorn Cabin, it was along a fork of Horseshoe Creek, from Sunny Pass looking north you would go down the pass and then turn left and go about 1/2 mile. I believe I was told that originally it was a trapper’s cabin from early 1900s that Forest Service took over and kept maintained. There was another cabin that was a sheepherder’s cabin to the north of there just before you got to Louden Lake. It was removed the year before I started and I hauled much of the wood from it over to the Bighorn Cabin for my stove fuel. {my added emphasis} It was a fantastic time for me living in the mountains and getting paid to hike in the scenery and talk to visitors. Like you I have many wonderful memories of my time there. Michael” POSTED BY: Wild Ranger on Jul 09, 2022 03:20 PM

Emmet apparently turned the Smith Family grazing permit back to the Forest Service by 1973 as his name does not appear in a USFS letter listing the six grazing permittees who grazed livestock in the Pasayten Wilderness in 1973.

A 1966 article about grazing within the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Land included: “Emmet estimates that in 66 years of use – 50 years under the Smith permit – the Basin has fattened at least 85,000 lambs with a value of $1 million , and produced 600,000 pounds of wool worth at least a quarter of a million dollars .”

Livestock grazing continued in the Pasayten Wilderness until at least 2001. In the 1990s, an increasing number of hikers and backpackers began to visit the Pasayten Wilderness. They complained about the effect of the grazing herds on the native vegetation and flowers, on the meadows full of sheep dung and the noise of the sheep. The Supervisor of the Okanogan National Forest wrote “today managing livestock in Wilderness is more challenging because of the attitudinal shifts occurring in our society”.

{The Re-Location of the Skull and Crossbones Lookout to Horseshoe Basin and the use of the cabin there is tied into the history of livestock grazing in the Pasayten Wilderness. It also reflects the nation’s changing attitude about the best use of publically owned lands. The story also includes the long and often contentious battle between the Forest Service and logging interests on one side and the National Park Service and conservationists over the creation of a North Cascades National Park.}

Our Visit to the Skull and Crossbones LO’s RE-LO Site in Horseshoe Basin ~ 7/14-16/2023

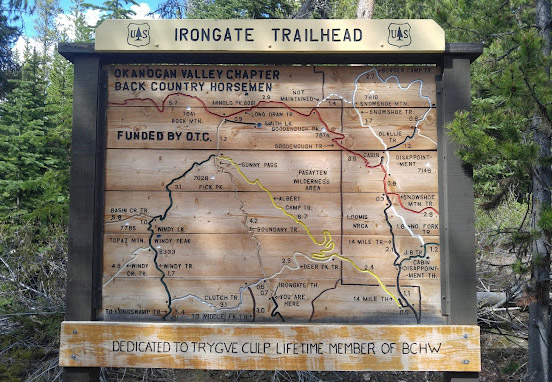

Peggy and I visited Horseshoe Basin on a short 3-day, 2-night backpack trip. We started at the Irongate Trailhead on July 14 and backpacked in that day to set up our tent in Sunny Basin at the old Sunny Camp. The next day we hiked, carrying only daypacks, into Horseshoe Basin. There, we searched for any remains of the re-located Skull and Crossbones Lookout cab. After exploring in Horseshoe Basin for the day, we returned to our camp in Sunny Basin. The following day, we backpacked back to our car at the Iron Gate Trailhead and drove to Omak to spend a night in a motel. The weather was sunny, with a range of mid 70s during the day to the low 40s at night during the Sunny Basin/Horseshoe Basin visit. It was an even 100 degrees when we got to Omak.

Most Horseshoe Basin visits begin at the Irongate Trailhead and almost all descriptions and trip reports start with the road to Irongate. The Washington Trails Association (WTA) web site states: “ Be warned, this road is quite rough — high clearance vehicles are necessary to negotiate it.” The road descriptions written in WTA trip reports vary from horrible to no big deal. A sample of these include: 1) ”Yes, the road in is indeed rough. In fact, calling parts of it a “road” is insulting to other roads.”; 2) “First off, the road. I flagged it as high clearance needed, but that isn’t strictly true. There aren’t many potholes, nor sections where you need a lot of approach/ departure. What there are however is lots of rocks you will need to drive up, and deep deep ruts to keep your tires out of. Getting stuck in a rut could be an issue, and I suppose a tall enough rock in the road might present some problems.”; 3) “Made the trek to the TH in a Honda Fit which does not have very high clearance. Some were surprised we made it but we never bottomed out once. …Do not believe the hype about the road – it was easy as long as you drive slowly and pick your line.” The differing opinions probably reflect each driver’s experience level in driving poorly maintained forest roads. I have driven on much worse roads chasing fire lookouts and trailheads. Segments of the road were badly eroded with deep ruts and big rocks and I appreciated the increased clearance and all-wheel drive of our Subaru Forester. It’s a shame that the Forest Service does not maintain this road better as it is obviously used by many hikers and others.

Day 1 ~ 7/14/2023:

Our first day started with a 2+ hour drive from Omak to the Iron Gate Trailhead. After eating an early lunch there, we began our back pack on the Boundary Trail at the Iron Gate Trailhead sign. The Boundary Trail follows the old service road to the Tungsten Mine as far as Sunny Pass. In the past, the drivable road extended ¾ mile beyond the current trailhead to the old Iron Gate Camp which was abandoned, along with that section of road in the 1960s.

The trail initially led through a flower-filled meadow. The route soon entered the shadeless remains of a lodgepole pine forest which had been burned by the 2006 Tripod Forest Fire. We then hiked through this “silver forest” for much of the rest of the day.

We initially slowly descended, losing 150 feet in the first 1 ½ miles. We then headed uphill on a gentle grade, gaining 1000 feet in the next three miles. We left the burnt snags behind after about 3 ½ miles as the trail led into green meadows.

As we neared Sunny Basin, we met Don, the volunteer wilderness ranger, who was headed downhill on patrol. We introduced ourselves to Don and learned that he was a fellow octogenarian. Don is a retired school teacher and has worked part-time for at least two multi-year periods for the Forest Service (one source says that he first worked for them first in 1961). A number of WTA Horseshoe Basin trip reports mentioned meeting Don and that he knew a lot about the history of the area. We talked with Don for a short time about the cabin. I gave him a copy of my draft writeup about the Skull and Crossbones LO re-location history. When I mentioned that we were going to search for the cabin site the next day, Don said that he did not think that we would find any remains. It turns out that Don had been the one who had previously written about also being the Horseshoe Basin wilderness ranger from 1973-1976. The cabin had been removed in 1972 and Don had hauled much of the wood from it to the Bighorn Cabin to be used for stove fuel. Don also told us that the windows and the shutters and hardware had all been carefully removed and packed out by the Forest Service.

After our visit with Don, we followed the trail up a steeper section with several switchbacks past two little streams to reach the green meadows of 6900 foot high Sunny Basin. After setting up camp here, we re-filled our water bottles, ate dinner and prepared for the first of two cool and windy nights here.

Day 2 ~ 7/15/2023:

The next morning, we headed out with light packs to search for the re-located lookout cabin site. The cabin was gone, but we had several bits of information to help us find the site:

1) In 1968, Harvey Manning had described the lookout cabin as being on a knoll beside a lovely meadow 4 ½ miles from the road-end at Iron Gate Camp.

2) Harvey also wrote that the meadow contained the Smith’s airstrip which was near the cabin. The meadow had been ditched for drainage and staked for boundaries to form the airstrip. While the airstrip was apparently last used about 50 years ago, there may still be some evidence of it remaining.

3) The 1965 USGS Horseshoe Basin map shows a structure near the north boundary of Section 15. I used this map to estimate the coordinates of this structure mark as N 48o 58.338’ W 119o 56.798’. (This location is about 5 ½ miles from the current road end, but the distance from where the pre-1960s road ended at the Old Iron Gate Camp would have been ¾ miles less.)

4) Several photos show the L-4 cab placed in the opening of a grove of trees. These photos were taken 50-60 years ago. Since trees grow and some die in that length of time, the site will not look exactly the same today. However the resemblance may be similar enough to help in the site verification.

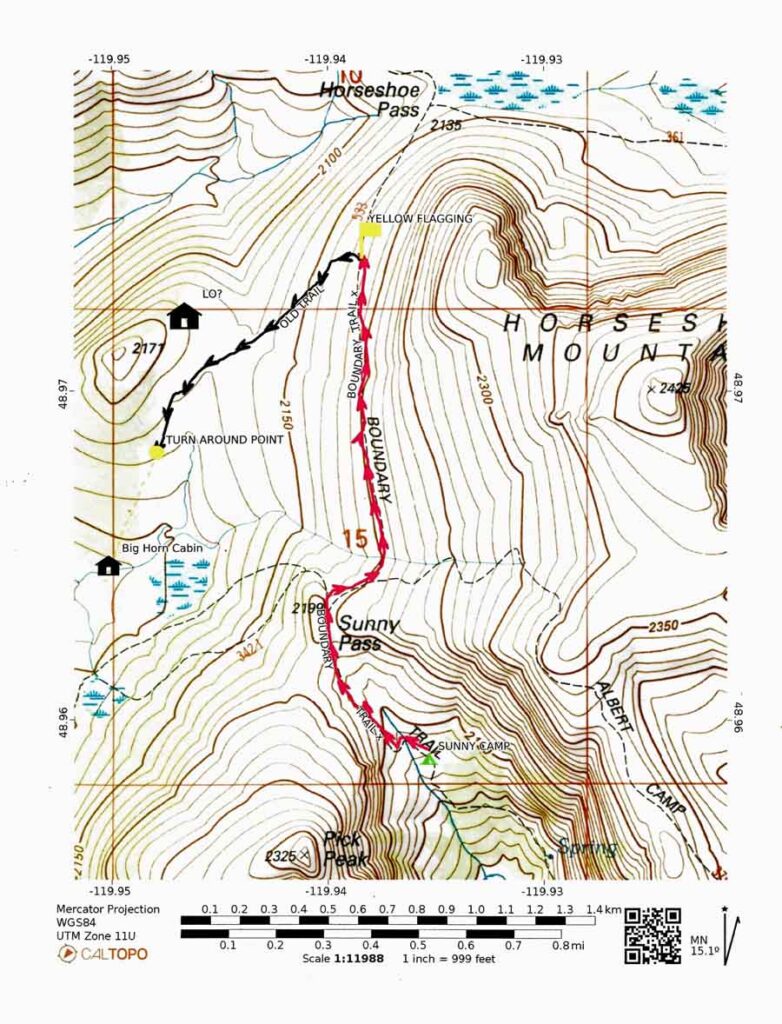

Today’s hike started with a ½ mile climb from our 6900’ elevation camp site in Sunny Basin to 7200’ Sunny Pass which is the entrance to the 7000+’ meadowlands and the 8000+’ peaks of Horseshoe Basin.

There was a trail intersection at Sunny Pass. The Boundary Trail bore right before turning north while the Windy Peak Trail soon turned sharp left. A comparison of two maps, one dated 1982 and one from 1965, shows that the current Boundary Trail did not exist during much of the time that the L-4 cab was in place. The old north-bound route turned left at Sunny Pass before turning north again near the Big Horn Cabin. The old trail passed close to the re-located Skull and Crossbones Lookout cab, while the newer trail is nearly ½ mile east of it.

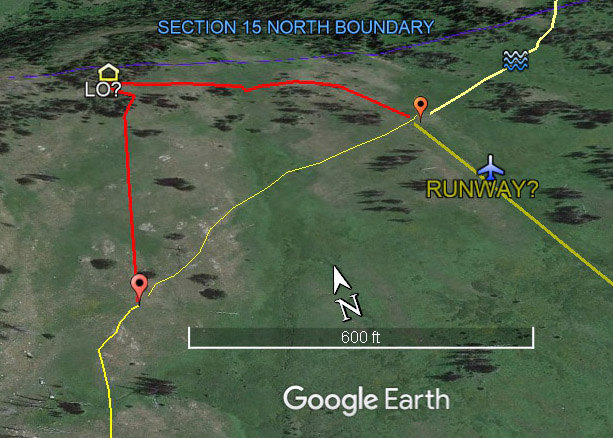

Don had stopped on his way back to his camp the previous evening to remind us that the cabin was not on the modern Boundary Trail, but had been near an older abandoned trail. He recommended that we follow the Boundary Trail north and then follow an old trail down into the basin. He offered to mark the spot where a faint trail dropping into the Basin could be seen. We took Don’s advice and continued north from Sunny Pass on the Boundary Trail as it contoured the lower slopes of Horseshoe Mountain.

The trees alongside the Boundary Trail blocked the view of the meadows, which were at an elevation 250’ lower than the trail, for much of the way. A photo taken from one of the trail’s open view-points shows the knoll that the cabin had been on and the lovely meadow below that Harvey Manning had described in 1968.

We reached Don’s yellow flagging about a mile after the Sunny Pass intersection. An old trail could be seen below us. We followed the old trail to the west and then to the southwest as it dropped into the Basin’s meadows below. When our track was downloaded onto a map, it appeared that we had been following the abandoned trail past the Big Horn Cabin that shows on the 1965 map.

We followed the old trail down into the meadows. It crossed a marshy wetlands and a dry ditch. It also crossed the head of two dry level areas. One of these might have been used as Emmet Smith’s landing strip. We saw none of the boundary stakes or other improvements described by Harvey Manning in 1968. Of course, the air strip had not been used for at least 50 years. A photo, which was taken toward the nearby knoll from one of these level areas, shows a number of bunches of tree similar to the re-located lookout cabin’s location shown in old photos.

We followed the old trail as it turned toward the south and headed toward the old Bighorn Cabin site. This led away from the estimated Skull and Crossbones Cabin site (shown as LO? on the Google Earth image) and into the zone burned by the 2006 Tripod Fire. We chose to turn around near the last of the unburnt trees along the trail.

After turning around, we left the old trail and followed a GPS track toward the coordinates of the LO? waypoint on the knoll above us. We checked each of the groves of trees along the way for signs of cabin remains. While we found no cabin remains during this search, the opening into the grove at our estimated location seemed to be the most likely site.

A 1969 photo showing Emmet Smith standing near the L-4 lookout cabin in place at Horseshoe Basin indicates that the cabin (14’ wide) with one of the shutters extended (another 5’) spanned the distance between two trees at the alcove opening into a grove of trees. My 5.5’ height was used as a “measuring stick” to estimate this 19’ distance on one of our photos of the likely site. This closely matched the distance between a live tree on one side and the remains of a dying tree on the other side. The trees behind the opening in our 2023 photo block the view of the mountains behind the cabin seen in the 1969 photo. The trees to the side are similar, but not identical. But, trees can grow, and die, during the 54 years between the time that the two photos were taken.

A 1955 photo of the L-4 Lookout cabin gives a glimpse into a storage area within the trees to the right of the cabin. This is closely matched by one of our photos of this same area. The high mountain ridge to the right is also similar in both photos.

After searching around this location for possible cabin remains, we walked down a grassy, tree-free corridor to meet the old trail near the probable landing strip location. Emmet’s short-field Stinson aircraft is seen parked near the cabin in several photos. This corridor would have provided a good taxiway from the airstrip to the cabin. We investigated several other potential cabin alcoves in the trees on the way down the knoll.

After reaching the old trail, we followed it and the Boundary Trail back to our camp in Sunny Basin where we spent a second night.

Don, the wilderness ranger, had predicted that we would find no remnants when he described the removal of the cabin by the Forest Service in the early 1970s. Even though we did not find any remains or obvious evidence showing the exact location of the Re-Located Skull and Crossbones Lookout cabin site, I was satisfied that we had visited the correct area. We had covered a large area around the location indicated on the 1965 map.

It is not surprising that we found no remaining evidence of either the Re-located Skull and Crossbones Lookout or Emmet Smith’s air strip during this day’s search. The U. S. Congress established the Pasayten Wilderness, which included Horseshoe Basin, in 1968. The enabling Public Law declared that the new wilderness was to be managed under the provisions of the 1964 Wilderness Act. The Wilderness Act defined a wilderness as an area untrammeled by man where man is a visitor who does not remain. The Act also declares that the wilderness is to be managed with no permanent improvements or human habitation. The Okanogan National Forest, within the Department of Agriculture, was given the responsibility of managing the Pasayten Wilderness. At the time of the 1968 creation of the Pasayten Wilderness, there were many man-made structures and other non-conforming uses within the area of the new wilderness. A Special Conditions section of the Wilderness Act allows continued non-conforming usage, such as grazing, use of aircraft or use of man-made structures within a Wilderness where these uses had been established before the Wilderness was designated by Congress. This continued usage was to be allowed subject to restrictions managed by the Secretary of Agriculture. One of the tasks for the Okanogan National Forest was to determine the extent of the non-conforming structures and usages within the Pasayten and to define how they were to be managed. The non-conforming livestock grazing along with Emmet Smith’s re-located lookout cabin and airstrip were evidently allowed within the Pasayten Wilderness under this Special Conditions section.

Even before the Pasayten Wilderness was designated, the Okanogan Forest Service had been under pressure by the North Cascades Conservation Council and other environmentalists to eliminate grazing in Horseshoe Basin. The groups were also pressuring the Forest Service to remove the cabin and airstrip which were being used by the holder of the grazing permit in the administration of his grazing allotment. Emmet Smith apparently gave up his grazing permit before 1973 as his name does not appear on a list of the six grazing permits still in existence in the Pasayten Wilderness in 1973. Since the only justification for the nonconforming cabin and airstrip was for the administration of Emmet’s grazing allotment, this would seem to require completely removing these “permanent improvements” and signs of “human habitation”.

Day 3 ~ 7/16/2023

After breakfast, we took down our tent, loaded up our backpacks and headed back down the Boundary Trail toward our car at the Iron Gate Trailhead. The trail was busier than it had been on our way in. We met a number of other backpackers and day hikers headed up toward Horseshoe Basin. Some of them asked to take our photo. Evidently they were not used to seeing slow octogenarian backpackers. We were honored to be described along with Don as “incredible people” in a July WTA trip report which reads in part: …” Met some incredible people along the way: an 87 & 84 year young couple who had backpacked up to Sunny Pass; a young woman solo hiking 45 miles in 3 days and last but not least Don M. the land steward for the Pasayten Wilderness. At 81, he continues to be a consistent supporter and volunteer of the area. He had been there a week when I came across him. Take the time to visit with him. He can fill you in with tons of history of the Pasayten Wilderness. “

Our visit to the Skull and Crossbones Lookout Site ~ 7/12/2023

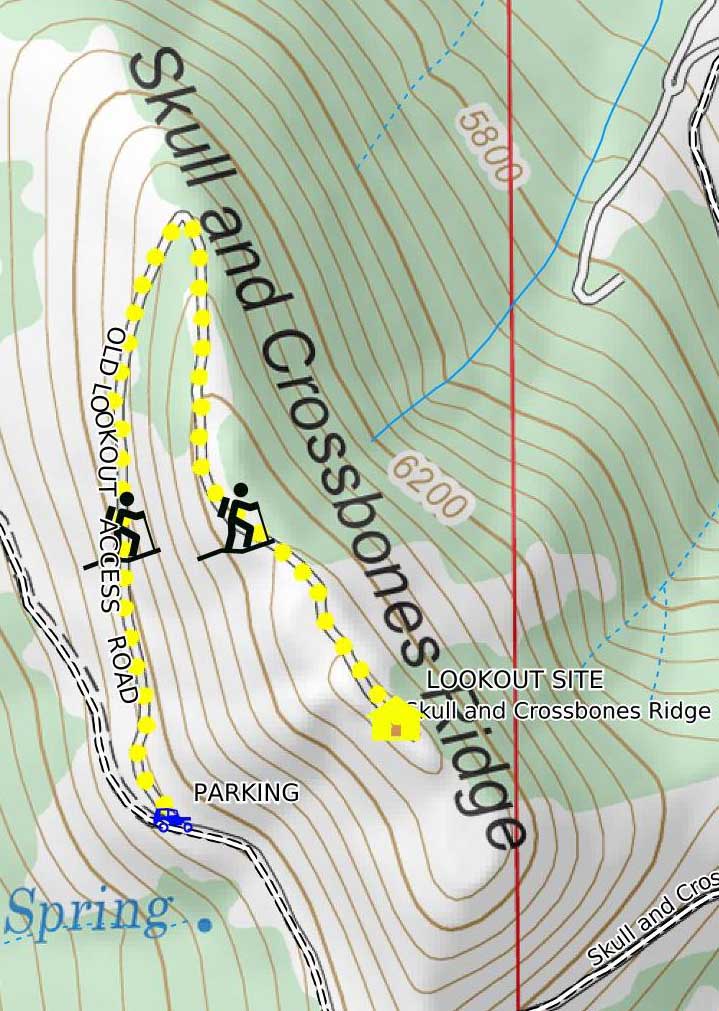

We visited Skull and Crossbones Ridge, the Origin Site for the L-4 Lookout Cab that had been moved to Horseshoe Basin by Emmet Smith in 1953. The first 50 miles of the 60+ mile drive from Omak was paved. The driving route continued on the good gravel South Fork Toats Coulee Road. The only questionable section of the drive was the last 1 ½ miles which was on the steep and narrow Cecil Creek Road. This dirt road could be slippery if wet. We parked our car at the bottom of the abandoned lookout access road and hiked up this road to the old lookout site.

We hiked up the abandoned lookout access road. It was less than one mile, with 350′ elevation gain, to the end of the road atop Skull and Crossbones Ridge. We found possible lookout artifacts (old boards and the remains of a low rock foundation wall) on a high point near the road end. Our GPS coordinates measured at this point were N 48o 49.380’W 119o 56.620’.

The Skull and Crossbones Ridge top stretched ½ mile on along a roughly north to south axis. There were several high points along its length. A camp was established on one of these high points about 1930. The L-4 lookout cab was built in 1932 on another of the high points to the south of the camp. The L-4 was then purchased by Emmet Smith on August 18, 1953 and moved to Horseshoe Basin later in 1953.

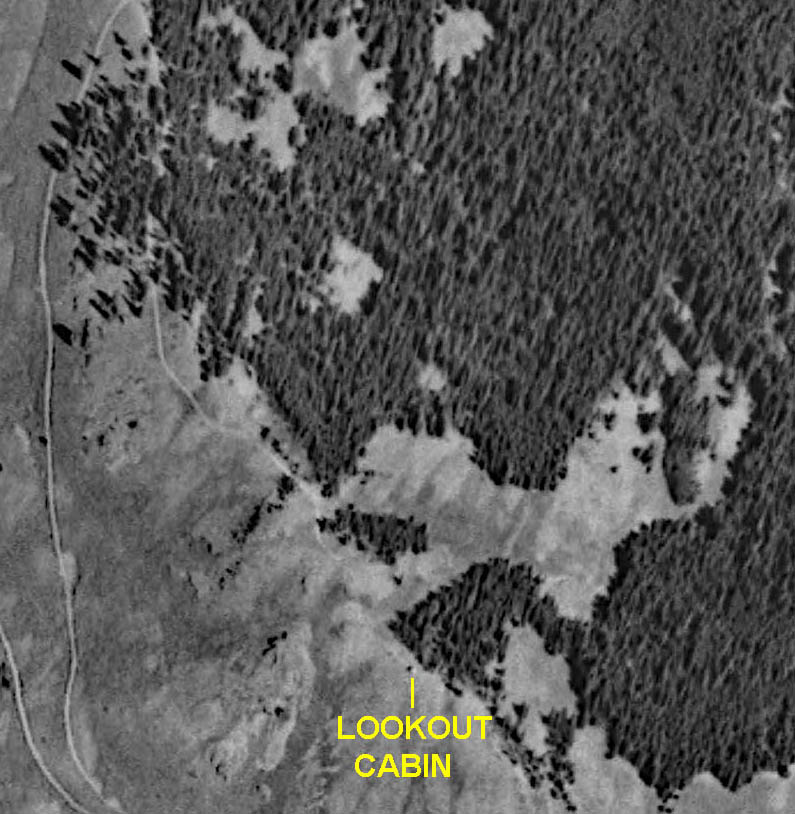

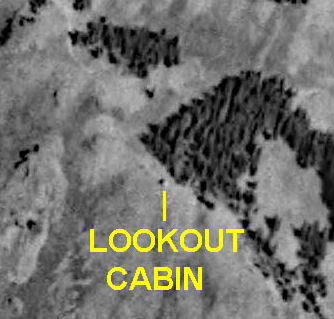

While we believed that the boards and rock foundation wall were remains of the L-4, it was possible that they were remains of the earlier camp. We looked at two aerial photos to help verify that these remains marked the site of the L-4 cab. The first image (shown below) was an aerial photo taken for the USGS during the period between July 2,1935 and August 11,1935. This image, which was taken shortly before the cab was purchased and moved, shows the L-4 still in place atop Skull and Crossbones Ridge. The cab was near a large open space in the heavily wooded eastern slopes of the ridge. The ridge top and slopes were no longer heavily wooded when we visited in 2023, so we were not able to visually match the site with the 1953 aerial image during our visit. The eastern slope was seen to be heavily wooded on a 2006 Google Earth aerial photo (also shown below). The large, distinctively shaped clearing and the clump of trees by the cabin shown on the 1953 photo could also be seen on the 2006 image. When a symbol was placed on the 2006 Google Earth image, using the GPs coordinates that I measured at the high point with the wood and rock foundation remains, this location showed a good match to the lookout cabin location shown on the 1953 image.

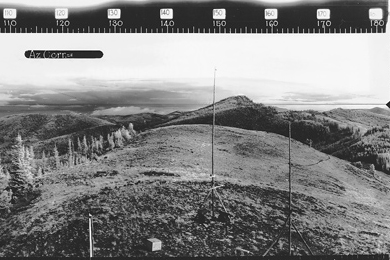

Photos taken from the lookout site, both to the northwest and to the southeast, show a ridgetop high point in each direction. These can be compared to similar views cropped from the panoramic photos that were taken from the roof of the lookout on September 9, 1934. The views to the northwest show the nearby high point that the 1930 camp sat on as well as the access road curving around it. The 1934 image also contains a car parked at the end of the road as well as a woodpile.

The southeasterly views contain Big Hill in the distance. Big Hill, also called Woodpile or Big Camp, was also used for fire detection in the 1930s. It blocks some of the view from the Skull and Crossbones Ridge so it was probably used as a patrol point by the Skull and Crossbones Lookout. The poles seen in the 1934 image likely are part of a telephone line. We found two segments of wire along the ridge top in that direction.

XX

After a last look at the 360 degree view from the Skull and Crossbones Ridge, we hiked down to our car and drove back to Omak to spend the night.